CATEGORIES

Categories

LBJ & NIXON SECRET PLOT TO KILL JFK!

Shocking truth finally revealed in newly released gov't documents

SIX MINUTES A DAY KEEPS ILLNESS AWAY!

FITNESS resolutions abound every new year — but experts say you may only need to exercise under six minutes daily while performing regular tasks to significantly cut your odds of experiencing conditions such as heart failure, stroke and heart attack!

ALEC & HILARIA TO RENEW VOWS FOR A PRICE!

Romance takes back seat as reality couple scripts their love

CHEW ON THIS: FOODS WE EAT ARE KILLING US!

WE ALL need food to live, but most of the stuff we eat in the American diet is killing us!

AUTHOR JOINS TEAM LIVELY IN BALDONI WAR!

More choose sides in smear campaign scandal

CLAWS OUT FOR STRAYING WOLVERINE!

Pals side with Hugh's ex-wife

CHALAMET READY TO QUIT ON KYLIE!

Can't switch off flirt machine as star soars

OZZY COMEBACK COULD KILL HIM!

CRIPPLED Ozzy Osbourne’s planning a miracle comeback concert, but sources say the Crazy Train singer currently struggles to stand and walk — leaving pals fearing his return will be his death!

MISERABLE MILESTONE FOR GARTH & TRISHA!

Sex scandal shreds their happiness

INES TAKES GLOVES OFF IN ANGIE WAR!

Tired of waiting around for Brad to be free of her

DEATH ROW FOR BANK EXECUTIONER!

Boasted that killing people was his dream come true

COUNTRY CARLY CHANGES TUNE TO PROTECT FRAGILE HEALTH

COUNTRY cutie Carly Pearce is raring to hit the road in February for her European tour — but sources spill that fans should expect the Every Little Thing singer’s shows to be less physical as she continues to battle lifethreatening heart disease!

GISELE TO TAP SHAKIRA FOR GODMOTHER!

NOW that singer Shakira has moved to the U.S., she and fellow South American Gisele Bündchen have grown so close that sources tell GLOBE the preggers supermodel wants the songbird to be her baby’s godmother!

KRASINSKI & CARELL'S OFFICE POLITICS!

Original cast wants reboot thrown in the circular file

ANGIE SHUNS DAD IN HIS FINAL DAYS!

Avoids Voight over politics & old wounds

What the Queen Really Thought of Meghan

The late Queen Elizabeth II’s closest confidants reveal the truth about her relationship with Meghan Markle

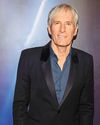

Doing Well After Brain Surgery

Michael Bolton is feeling positive about the year ahead.

Timothée's WANDERING EYE

Problem, or part of his charm? Timothée Chalamet has been schmoozing up a storm while promoting his Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown — and a source says his naturally flirtatious demeanor is well known around Hollywood.

Hollywood Backs Blake

After nearly getting canceled over It Ends With Us, Blake Lively exacts revenge on Justin Baldoni

BLAKE BREAKS HER SILENCE

Five months after feud rumors first exploded, Blake Lively and Justin Baldoni file shocking lawsuits!

Harry CAUGHT IN A SCANDAL

In 2021, Prince Harry signed on as \"chief impact officer\" of BetterUp, \"a coaching and mental health app that he, himself, has used in the past.

It's Our Most Chaotic Season!

Welcome back to Charleston! The cast of the Bravo show share some sweet tea on big changes in Season 10

THE DARK SIDE OF ONLYFANS

The price of sharing intimate content on the subscription platform can be steep

ADVICE QUEEN MEL ROBBINS - Learning to LET GO

BEFORE TELLING MILLIONS HOW TO FIND CONTENTMENT, THE POPULAR PODCASTER HAD TO FACE HER OWN DEMONS.

JAMIE LEE CURTIS Why I've NEVER BEEN HAPPIER!

THE ACCOLADES KEEP COMING AS THE ACTRESS ENJOYS THE MOST PRODUCTIVE TIME OF HER LIFE

P.K. & DORIT: THE TRUTH ABOUT HIS DRINKING

Don’t call him a “full-blown alcoholic”! The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills’ P.K. Kemsley is defensive that his estranged wife, Dorit, 48, blames him for the demise of their marriage.

Kate's HOLIDAY COMEBACK

AFTER A DIFFICULT YEAR, THE PRINCESS OF WALES LOOKED FIT AS THE ROYAL FAMILY CELEBRATED THEIR CHRISTMAS TRADITIONS.

THE Ugly Truth

INSIDE BLAKE LIVELY'S SHOCKING ALLEGATIONS AGAINST HER IT ENDS WITH US DIRECTOR AND COSTAR JUSTIN BALDONI - PLUS, HIS PLANS FOR REVENGE!

IT'S OVER! (SORTA)

Eight years after Angelina Jolie filed for divorce from Brad Pitt, the exes have finally reached a settlement.

JOLIE PUTS HER KIDS TO WORK!

CASH-CONSCIOUS Angelina Jolie is drowning in bills from her nasty legal battles with ex-husband Brad Pitt — and now she’s encouraging their six kids to earn their own dough, tipsters tell GLOBE.