VAST and impersonal country houses, built to create an impression on visitors rather than bestow creature comforts on inhabitants, had been a feature of the English landscape long before Blenheim Palace. Yet this huge complex, the house alone encompassing seven acres of Oxfordshire on completion in 1725, bore comparison with the largest palaces of Europe. Set to become the historic seat of the Dukes of Marlborough after Queen Anne gifted the manor of Woodstock to the 1st Duke, John Churchill, in 1705, as a reward for his military triumphs, it’s the only English country house—those of bishops aside—that has by longstanding popular consent been accorded the honorific title of palace (it was once described by some as Blenheim Castle). It is the only one to be included on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites, which places it in the company of Stonehenge, the Tower of London and the cathedrals of Canterbury and Durham for what is seen as its priceless expression of facets of our national culture.

Sir John Vanbrugh (1664–1726), its prime creator, already knew how to think big. Like Sir Christopher Wren, Vanbrugh was a late entrant to the architectural profession, being aged 35 when he was handed his first commission, Castle Howard in North Yorkshire, for the Earl of Carlisle in 1699. At a stroke, that splendid creation established him as the leading exponent of British Baroque, grandiose in style, romantic in spirit.

هذه القصة مأخوذة من طبعة September 15, 2021 من Country Life UK.

ابدأ النسخة التجريبية المجانية من Magzter GOLD لمدة 7 أيام للوصول إلى آلاف القصص المتميزة المنسقة وأكثر من 9,000 مجلة وصحيفة.

بالفعل مشترك ? تسجيل الدخول

هذه القصة مأخوذة من طبعة September 15, 2021 من Country Life UK.

ابدأ النسخة التجريبية المجانية من Magzter GOLD لمدة 7 أيام للوصول إلى آلاف القصص المتميزة المنسقة وأكثر من 9,000 مجلة وصحيفة.

بالفعل مشترك? تسجيل الدخول

Save our family farms

IT Tremains to be seen whether the Government will listen to the more than 20,000 farming people who thronged Whitehall in central London on November 19 to protest against changes to inheritance tax that could destroy countless family farms, but the impact of the good-hearted, sombre crowds was immediate and positive.

A very good dog

THE Spanish Pointer (1766–68) by Stubbs, a landmark painting in that it is the artist’s first depiction of a dog, has only been exhibited once in the 250 years since it was painted.

The great astral sneeze

Aurora Borealis, linked to celestial reindeer, firefoxes and assassinations, is one of Nature's most mesmerising, if fickle displays and has made headlines this year. Harry Pearson finds out why

'What a good boy am I'

We think of them as the stuff of childhood, but nursery rhymes such as Little Jack Horner tell tales of decidedly adult carryings-on, discovers Ian Morton

Forever a chorister

The music-and way of living-of the cabaret performer Kit Hesketh-Harvey was rooted in his upbringing as a cathedral chorister, as his sister, Sarah Sands, discovered after his death

Best of British

In this collection of short (5,000-6,000-word) pen portraits, writes the author, 'I wanted to present a number of \"Great British Commanders\" as individuals; not because I am a devotee of the \"great man, or woman, school of history\", but simply because the task is interesting.' It is, and so are Michael Clarke's choices.

Old habits die hard

Once an antique dealer, always an antique dealer, even well into retirement age, as a crop of interesting sales past and future proves

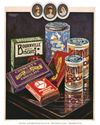

It takes the biscuit

Biscuit tins, with their whimsical shapes and delightful motifs, spark nostalgic memories of grandmother's sweet tea, but they are a remarkably recent invention. Matthew Dennison pays tribute to the ingenious Victorians who devised them

It's always darkest before the dawn

After witnessing a particularly lacklustre and insipid dawn on a leaden November day, John Lewis-Stempel takes solace in the fleeting appearance of a rare black fox and a kestrel in hot pursuit of a pipistrelle bat

Tarrying in the mulberry shade

On a visit to the Gainsborough Museum in Sudbury, Suffolk, in August, I lost my husband for half an hour and began to get nervous. Fortunately, an attendant had spotted him vanishing under the cloak of the old mulberry tree in the garden.