WILLIAM MORRIS championed such an extraordinarily diverse range of Arts and interests that making an exact classification of him is difficult to achieve. A poet, romance writer, critic, socialist reformer, scholar and, above all, a prolific designer, he was a man for whom the word polymath was coined.

Born in Walthamstow on March 24, 1834, he was the third child and eldest son of a highly successful city broker. The family enjoyed a privileged lifestyle, settling at the Woodford Hall estate in Essex. By all accounts, Morris was an indulged child, who is said to have enjoyed wearing a miniature copy of a medieval suit of armour when riding his Shetland pony in Epping Forest.

At the age of eight, his father took him to Canterbury Cathedral, an experience that he later described as feeling as if the gates of Heaven had opened for him. The memory of this first visit certainly seems to have remained in his mind, as, when he became involved with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), which he called the ‘anti scrapes’, his first project was the restoration of Canterbury’s choir.

Young William spent his time visiting churches and forests and enthusiastically reading the novels of Sir Walter Scott, all childhood pursuits that surely helped in the development of his love of Nature and historical romance. Indeed, his ideas pertaining to design were firmly established by the time he was 16. During a visit to London in 1851, Morris refused to go to the Great Exhibition in the Crystal Palace, because its emphasis on mass-produced goods was contrary to his belief in traditional craftsmanship.

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der September 08, 2021-Ausgabe von Country Life UK.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent ? Anmelden

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der September 08, 2021-Ausgabe von Country Life UK.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent? Anmelden

Save our family farms

IT Tremains to be seen whether the Government will listen to the more than 20,000 farming people who thronged Whitehall in central London on November 19 to protest against changes to inheritance tax that could destroy countless family farms, but the impact of the good-hearted, sombre crowds was immediate and positive.

A very good dog

THE Spanish Pointer (1766–68) by Stubbs, a landmark painting in that it is the artist’s first depiction of a dog, has only been exhibited once in the 250 years since it was painted.

The great astral sneeze

Aurora Borealis, linked to celestial reindeer, firefoxes and assassinations, is one of Nature's most mesmerising, if fickle displays and has made headlines this year. Harry Pearson finds out why

'What a good boy am I'

We think of them as the stuff of childhood, but nursery rhymes such as Little Jack Horner tell tales of decidedly adult carryings-on, discovers Ian Morton

Forever a chorister

The music-and way of living-of the cabaret performer Kit Hesketh-Harvey was rooted in his upbringing as a cathedral chorister, as his sister, Sarah Sands, discovered after his death

Best of British

In this collection of short (5,000-6,000-word) pen portraits, writes the author, 'I wanted to present a number of \"Great British Commanders\" as individuals; not because I am a devotee of the \"great man, or woman, school of history\", but simply because the task is interesting.' It is, and so are Michael Clarke's choices.

Old habits die hard

Once an antique dealer, always an antique dealer, even well into retirement age, as a crop of interesting sales past and future proves

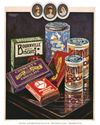

It takes the biscuit

Biscuit tins, with their whimsical shapes and delightful motifs, spark nostalgic memories of grandmother's sweet tea, but they are a remarkably recent invention. Matthew Dennison pays tribute to the ingenious Victorians who devised them

It's always darkest before the dawn

After witnessing a particularly lacklustre and insipid dawn on a leaden November day, John Lewis-Stempel takes solace in the fleeting appearance of a rare black fox and a kestrel in hot pursuit of a pipistrelle bat

Tarrying in the mulberry shade

On a visit to the Gainsborough Museum in Sudbury, Suffolk, in August, I lost my husband for half an hour and began to get nervous. Fortunately, an attendant had spotted him vanishing under the cloak of the old mulberry tree in the garden.