And what would happen if it actually works

Like a little white Lazarus with red eyes, the paralyzed mouse was walking again.

A few days earlier, the mouse had been sprawled on an operating table while two Chinese graduate students peered through a microscope and operated on its spine. With a tiny pair of scissors, they removed the top half of a fingernail-thin vertebra, exposing a gleaming patch of spinal-cord tissue. It looked like a Rothko, a clean ivory rectangle bisected by a red line. Cautiously—the mouse occasionally twitched—they snipped the red line (an artery) and tied it off. Then one student reached for a $1,000 scalpel with a diamond blade so thin that it was transparent. With a quick slice of the spinal cord, the mouse’s back legs were rendered forever useless.

Or they would have been, except that the other student immediately doused the wound with a faintly amber fluid, like the last drop of watered-down scotch. The fluid contained a chemical called polyethylene glycol, or peg, and as the students stitched the mouse back up, the chemical began to stitch the animal’s nerve cells back together.

Two days later, the mouse was walking. Not perfectly—its back legs lurched at times. But compared with a control mouse nearby—which had undergone the same surgery, minus the peg, and was now dragging its dead back legs behind itself—it puttered around brilliantly, sniffng every corner of its cage.

If peg ever proves effective in humans, it will be a near-miraculous therapy: Despite spending many millions of dollars on research over the past century, doctors have no way to repair damaged spinal cords. But that’s not the only reason the man directing this research—a surgeon in Harbin, China, named Xiaoping Ren—has been garnering attention in scientific circles.

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der September 2016-Ausgabe von The Atlantic.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent ? Anmelden

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der September 2016-Ausgabe von The Atlantic.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent? Anmelden

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

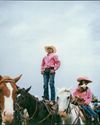

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.