When Beatriz Flamini was growing up, in Madrid, she spent a lot of time alone in her bedroom. "I really liked being there," she says. She'd read books to her dolls and write on a chalkboard while giving them lessons in math or history.

As she got older, she told me, she sometimes imagined being a professor like Indiana Jones: the kind who slipped away from the classroom to "be who he really was." In the early nineteen-nineties, while Flamini was studying to be a sports instructor, she visited a cave for the first time. She and a friend drove north of Madrid to El Reguerillo, a cavern known for its paleolithic engravings. "We stayed until Sunday and came out only because we had classes and work," Flamini recalls. El Reguerillo was dark but cozy, and inside its walls she experienced an overwhelming sense of love. "There were no words for what I felt," she says.

After graduating, Flamini taught aerobics in Madrid. She was admired for her charisma and commitment. "Everyone wanted me for their classes," she says. "They fought over me." By the time she turned forty, in 2013, she had a partner, a car, and a house. But she felt unsatisfied. She didn't really care about financial stability, and, unlike most people she knew, she didn't want children. She experienced an existential crisis. "You know you're going to die-today, tomorrow, within fifty years," Flamini told herself. "What is it that you want to do with your life before that happens?" The immediate answer, she remembers, was to "grab my knapsack and go and live in the mountains."

Flamini moved to the Sierra de Gredos, in central Spain, where she worked as a caretaker at a mountain refuge. She became certified in safety protocols for working on tall structures, and she learned first-aid skills, specializing in retrieving people from deep crevices and other perilous locations.

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der January 29, 2024-Ausgabe von The New Yorker.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent ? Anmelden

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der January 29, 2024-Ausgabe von The New Yorker.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent? Anmelden

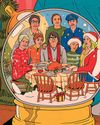

YULE RULES

“Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point.”

COLLISION COURSE

In Devika Rege’ first novel, India enters a troubling new era.

NEW CHAPTER

Is the twentieth-century novel a genre unto itself?

STUCK ON YOU

Pain and pleasure at a tattoo convention.

HEAVY SNOW HAN KANG

Kyungha-ya. That was the entirety of Inseon’s message: my name.

REPRISE

Reckoning with Donald Trump's return to power.

WHAT'S YOUR PARENTING-FAILURE STYLE?

Whether you’re horrifying your teen with nauseating sex-ed analogies or watching TikToks while your toddler eats a bagel from the subway floor, face it: you’re flailing in the vast chasm of your child’s relentless needs.

COLOR INSTINCT

Jadé Fadojutimi, a British painter, sees the world through a prism.

THE FAMILY PLAN

The pro-life movement’ new playbook.

President for Sale - A survey of today's political ads.

On a mid-October Sunday not long ago sun high, wind cool-I was in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, for a book festival, and I took a stroll. There were few people on the streets-like the population of a lot of capital cities, Harrisburg's swells on weekdays with lawyers and lobbyists and legislative staffers, and dwindles on the weekends. But, on the façades of small businesses and in the doorways of private homes, I could see evidence of political activity. Across from the sparkling Susquehanna River, there was a row of Democratic lawn signs: Malcolm Kenyatta for auditor general, Bob Casey for U.S. Senate, and, most important, in white letters atop a periwinkle not unlike that of the sky, Kamala Harris for President.