On New Year’s Day 2020, I was zipping up my fleece to head outside when the phone in the kitchen rang. I picked it up to find a reporter on the line. “Dr. Fauci,” he said, “there’s something strange going on in Central China. I’m hearing that a bunch of people have some kind of pneumonia. I’m wondering, have you heard anything?” I thought he was probably referring to influenza, or maybe a return of SARS, which in 2002 and 2003 had infected about 8,000 people and killed more than 750. SARS had been bad, particularly in Hong Kong, but it could have been much, much worse.

A reporter calling me at home on a holiday about a possible disease outbreak was concerning, but not that unusual. The press sometimes had better, or at least faster, ground-level sources than I did as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and reporters were often the first to pick up on a new disease or situation. I told the reporter that I hadn’t heard anything, but that we would monitor the situation.

Monitoring, however, was not easy. For one thing, we had a hard time finding out what was really going on in China because doctors and scientists there appeared to be afraid to speak openly, for fear of retribution by the Chinese government.

In the first few days of 2020, the word coming out of Wuhan—a city of more than 11 million— suggested that the virus did not spread easily from human to human. Bob Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, was already in contact with George Gao, his counterpart in China. During an early-January phone call, Bob reported that Gao had assured him that the situation was under control. A subsequent phone call was very different. Gao was clearly upset, Bob said, and told him that it was bad—much, much worse than people imagined.

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der July - August 2024-Ausgabe von The Atlantic.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent ? Anmelden

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der July - August 2024-Ausgabe von The Atlantic.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent? Anmelden

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

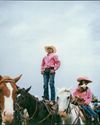

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.