In June, the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Roe vs Wade, a landmark decision that had made abortion a constitutional right in the country. Given this massive setback to reproductive rights in the world's oldest democracy, many in India took the opportunity to congratulate themselves on having more progressive abortion laws. The next month, however, the Delhi high court refused a 25-year-old woman the right to terminate her pregnancy because she was unmarried. The high court bench was interpreting the main abortion law the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, 1971-which allowed certain categories of women the right to abortion under very specific conditions. The judges argued that, in her case, aborting the foetus would be equivalent to "killing the child." On 29 September, the Supreme Court of India stepped in to expand the right to cover "unmarried women," whom the MTP Act did not until then explicitly include.

"Certain constitutional values, such as the right to reproductive autonomy, the right to live a dignified life, the right to equality, and the right to privacy have animated our interpretation of the MTP Act and the MTP Rule," the judgment states.

While this is a step in the right direction and is remarkable for upholding a comprehensive view of women's rights, it is in stark contrast to how India got its abortion law, which was not exactly created keeping women's reproductive autonomy in mind. Unlike in several other parts of the world, our abortion law did not emerge as a result of feminist interventions that placed women's political, social and sexual autonomy at their centre. Instead, in India, women's reproductive fate has always been tied up with government anxieties about population control. After Independence, family planning became a central plank in India's developmental ambitions and, to that end, the regulation of women's fertility was treated as a national imperative.

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der October 2022-Ausgabe von The Caravan.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent ? Anmelden

Diese Geschichte stammt aus der October 2022-Ausgabe von The Caravan.

Starten Sie Ihre 7-tägige kostenlose Testversion von Magzter GOLD, um auf Tausende kuratierte Premium-Storys sowie über 8.000 Zeitschriften und Zeitungen zuzugreifen.

Bereits Abonnent? Anmelden

Mob Mentality

How the Modi government fuels a dangerous vigilantism

RIP TIDES

Shahidul Alam’s exploration of Bangladeshi photography and activism

Trickle-down Effect

Nepal–India tensions have advanced from the diplomatic level to the public sphere

Editor's Pick

ON 23 SEPTEMBER 1950, the diplomat Ralph Bunche, seen here addressing the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The first black Nobel laureate, Bunche was awarded the prize for his efforts in ending the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

Shades of The Grey

A Pune bakery rejects the rigid binaries of everyday life / Gender

Scorched Hearths

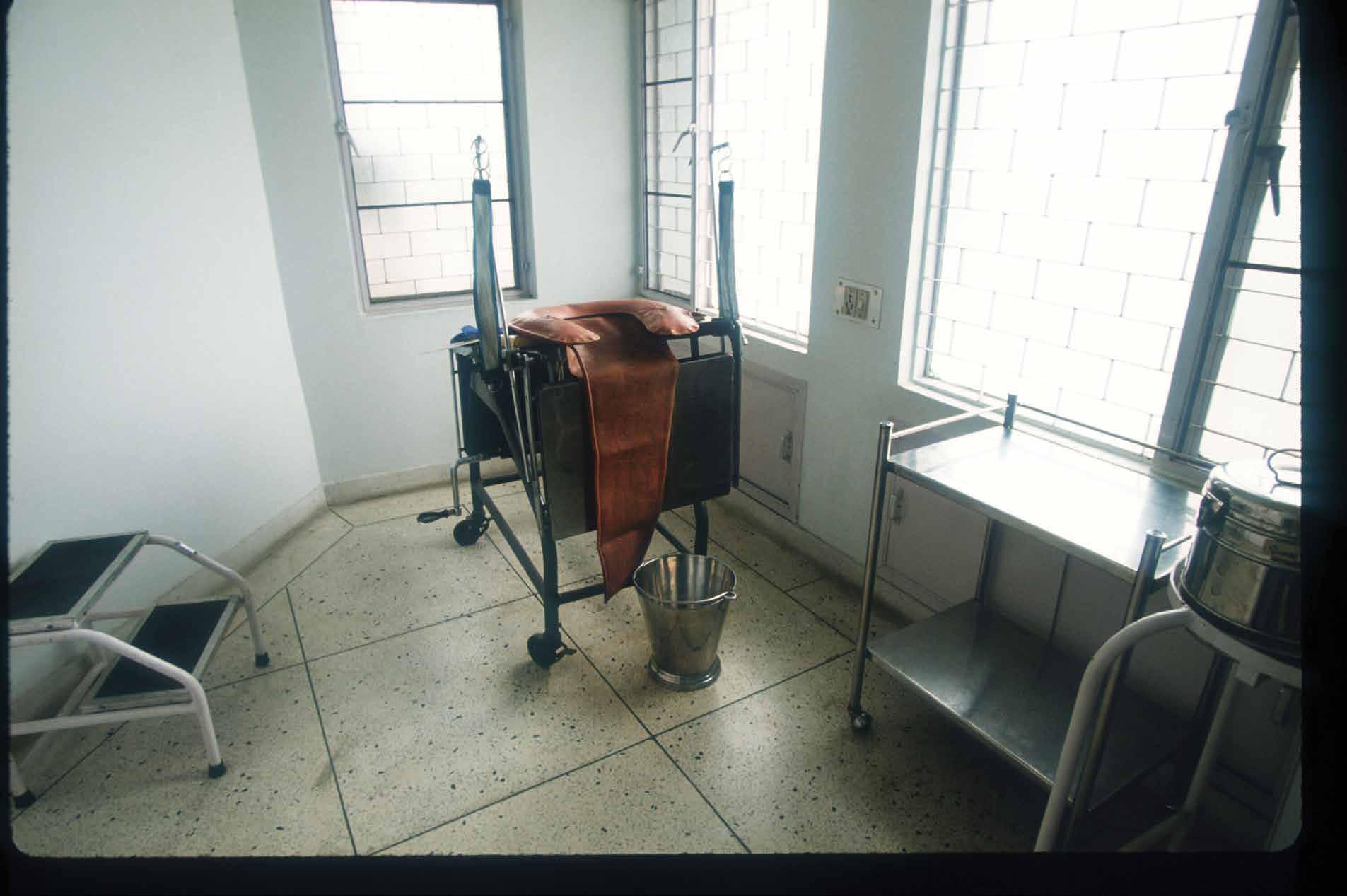

A photographer-nurse recalls the Delhi violence

Licence to Kill

A photojournalist’s account of documenting the Delhi violence

CRIME AND PREJUDICE

The BJP and Delhi Police’s hand in the Delhi violence

Bled Dry

How India exploits health workers

The Bookshelf: The Man Who Learnt To Fly But Could Not Land

This 2013 novel, newly translated, follows the trajectory of its protagonist, KTN Kottoor.