In fact, each of the six churches he designed after the Act of 1711, which authorised the building of new places of worship for London’s expanding population, carries a fascination of its own. Most importantly, they still function as places of worship, but, for the casual visitor, it is their exteriors that leave a lasting impression. As Owen Hopkins, author of From the Shadows: The Architecture and Afterlife of Nicholas Hawksmoor, has written: ‘Colossal in scale, of brilliant white stone, stark and austere in design yet resonant with allusions to architecture distant in time and place, these churches still dominate their areas even as the city has grown around them.’

South of the Thames, St Alfege, Greenwich, on which construction work finished in 1714, was the first, its demonstration of Hawksmoor’s capacity for overwhelming massiveness somewhat offset by John James’s graceful tower. The other five are north of the river. Of his three Stepney churches, St Anne’s, Limehouse, is cliff-like and rather sinister. Once standing in fields running down to the Thames, for years this giant structure also served as a shipping navigation point. St George-in-the-East, at the bottom of Cannon Street Road, is similarly eerie, with creepy octagonal turrets and a pervading air of gloom.

Discovering a genius

For years, Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661– 1736) was damned as the low-born assistant of Sir Christopher Wren and Sir John Vanbrugh (he assisted in the design of Wren’s St Paul’s and his City churches, and of Vanbrugh’s Castle Howard in North Yorkshire) and an inferior architect. His six London churches were the most important body of work undertaken in his own name.

Esta historia es de la edición February 09, 2022 de Country Life UK.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición February 09, 2022 de Country Life UK.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

Save our family farms

IT Tremains to be seen whether the Government will listen to the more than 20,000 farming people who thronged Whitehall in central London on November 19 to protest against changes to inheritance tax that could destroy countless family farms, but the impact of the good-hearted, sombre crowds was immediate and positive.

A very good dog

THE Spanish Pointer (1766–68) by Stubbs, a landmark painting in that it is the artist’s first depiction of a dog, has only been exhibited once in the 250 years since it was painted.

The great astral sneeze

Aurora Borealis, linked to celestial reindeer, firefoxes and assassinations, is one of Nature's most mesmerising, if fickle displays and has made headlines this year. Harry Pearson finds out why

'What a good boy am I'

We think of them as the stuff of childhood, but nursery rhymes such as Little Jack Horner tell tales of decidedly adult carryings-on, discovers Ian Morton

Forever a chorister

The music-and way of living-of the cabaret performer Kit Hesketh-Harvey was rooted in his upbringing as a cathedral chorister, as his sister, Sarah Sands, discovered after his death

Best of British

In this collection of short (5,000-6,000-word) pen portraits, writes the author, 'I wanted to present a number of \"Great British Commanders\" as individuals; not because I am a devotee of the \"great man, or woman, school of history\", but simply because the task is interesting.' It is, and so are Michael Clarke's choices.

Old habits die hard

Once an antique dealer, always an antique dealer, even well into retirement age, as a crop of interesting sales past and future proves

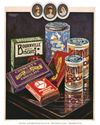

It takes the biscuit

Biscuit tins, with their whimsical shapes and delightful motifs, spark nostalgic memories of grandmother's sweet tea, but they are a remarkably recent invention. Matthew Dennison pays tribute to the ingenious Victorians who devised them

It's always darkest before the dawn

After witnessing a particularly lacklustre and insipid dawn on a leaden November day, John Lewis-Stempel takes solace in the fleeting appearance of a rare black fox and a kestrel in hot pursuit of a pipistrelle bat

Tarrying in the mulberry shade

On a visit to the Gainsborough Museum in Sudbury, Suffolk, in August, I lost my husband for half an hour and began to get nervous. Fortunately, an attendant had spotted him vanishing under the cloak of the old mulberry tree in the garden.