The primary reason for annealing rifle brass is to prevent case necks from cracking – and they will, eventually, because firing and resizing cases “work hardens” brass, making the thin necks brittle. Most rifle cases will survive four or five firings, and some will last longer, depending on the brand and method of resizing. Many handloaders avoid the issue entirely by retiring brass after several firings.

I did this for many years, selling well-fired cases for scrap at a local recycling center, using the money as partial payment for new brass. This worked fine back when bulk brass was widely available and relatively inexpensive, but that started changing several years ago, when demand for ammunition and components rose enormously during the Obama administration.

Some companies that sold bulk brass also happened to be major ammunition manufacturers. When demand for ammunition rose, they found it more sensible to use new cases to make ammunition. As a result, it wasn’t always possible to buy a batch of new brass, so many handloaders decided to make their old brass last longer. This coincided with an ongoing trend toward handloading for finer accuracy, whether because more shooters started competing in a target game, shot at longer ranges or decided .5-inch groups were necessary for slaying white-tailed deer because our hunting buddies bragged about their tiny groups. Many handloaders discovered that paying a premium for more consistent brass, or “uniforming” common brass, resulted in finer accuracy. They didn’t want to toss expensive or reworked cases after a few firings, so they started annealing.

I started annealing before the recent shortages, primarily due to fooling with wildcat cartridges. Forming wildcat cases required both time and, often, the expense of fire forming, but I was somewhat startled to find that annealing wasn’t very complicated or time-consuming. This surprise was due to the standard misinformation published for many years, which went something like this: “Stand your fired cases in a metal pan, then pour enough cold water into the pan to cover everything but the shoulders and necks. Heat the brass with a torch until it glows red, then knock the cases over into the water, quenching the hot brass to finish the annealing process.”

Esta historia es de la edición June - July 2017 de Handloader.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición June - July 2017 de Handloader.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

OEHLER's New System 89 Chronograph

Measuring Bullet Performance Downrange

The Problem with Low Pressure Loads

Bullets & Brass

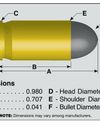

Measurements for Rifle Handloading

Handy Techniques for Accurate Ammunition

THE BRASS RING

In Range

Semi-custom Bullet Moulds

Mike's Shoot in' Shack

REVISITING THE 6.5 -06 A-SQUARE

Loading New Bullets and Powders

Cimarron Stainless Frontier .45 Colt

From the Hip

9x18mm Makarov

Cartridge Board

Alliant 20/28

Propellant Profiles

.224 Clark

Wildcat Cartridges