TO EXPERIENCE A THING as beautiful means: to experience it necessarily wrongly,” Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in The Will to Power. It is a line that Susan Sontag quotes toward the end of her 1977 essay collection, On Photography, about how photographs aestheticize misery. It is a line that Sontag’s authorized biographer, Benjamin Moser, quotes to describe Sontag’s susceptibility to beautiful, but punishing, lovers. And it is a line that I am quoting to summarize how Moser’s monumental and stylish biography, Sontag: Her Life and Work, fails its subject—a woman whose beauty, and the sex appeal and celebrity that went along with it, Moser insists upon to the point of occluding what makes her so deeply interesting.

The fascination of Sontag lies in her endurance as a cultural icon, the model of how a woman should think and write in public, even though her thinking and writing weren’t very rigorous. What is intriguing about Sontag is less who she was than how we understand our desire for her, or someone like her, to occupy a rare position in American literary culture: that of a dark-haired, dark-eyed, apparently invulnerable woman capable of transforming intellectual seriousness into an erotic spectacle. What need does such a presence and performance satisfy?

Esta historia es de la edición October 2019 de The Atlantic.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición October 2019 de The Atlantic.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

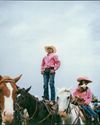

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.