For more than a decade, Tom Insel was the director of the National Institute of Mental Health, which made him one of the most influential psychiatrists in the world. But, frustrated by psychiatry’s inability to effectively help people suffering from mental illness, he began to question some of the basic premises of his field. So he left for Silicon Valley, where he’s trying to use smartphones to reduce the world’s mental anguish.

Sometime around 2010, about two-thirds of the way through his 13 years at the helm of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)—the world’s largest mental-health research institution—Tom Insel started speaking with unusual frankness about how both psychiatry and his own institute were failing to help the mentally ill. Insel, runner-trim, quietly alert, and constitutionally diplomatic, did not rant about this. It’s not in him. You won’t hear him trash-talk colleagues or critics.

Yet within the bounds of his unbroken civility, Insel began voicing something between a regret and an indictment. In writings and public talks, he lamented the pharmaceutical industry’s failure to develop effective new drugs for depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia; academic psychiatry’s overly cozy relationship with Big Pharma; and the paucity of treatments produced by the billions of dollars the NIMH had spent during his tenure. He blogged about the failure of psychiatry’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders to provide a productive theoretical basis for research, then had the NIMH ditch the DSM altogether—a decision that roiled the psychiatric establishment. Perhaps most startling, he began opening public talks by showing charts that revealed psychiatry as an underachieving laggard: While medical advances in the previous half century had reduced mortality rates from childhood leukemia, heart disease, and aids by 50 percent or more, they had failed to reduce suicide or disability from depression or schizophrenia.

“You’ll think that I probably ought to be fired,” he would tell audiences, “and I can certainly understand that.”

Esta historia es de la edición July/August 2017 de The Atlantic.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición July/August 2017 de The Atlantic.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

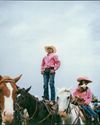

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.