Like many places in America where abortions are performed, the Blue Mountain Clinic, in Missoula, Montana, has faced a litany of threats. Protesters have routinely harassed patients since the facility opened, in the late seventies. In 1993, a firebomb gutted the premises. The clinic eventually reopened at a new location, in a building fortified with bulletproof windows and thick concrete walls. On June 24th of last year, staff members gathered there to console one another following a different sort of attack: the Supreme Court had just issued a final ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, overturning Roe v. Wade and eliminating the constitutional right to abortion. Working at an abortion clinic requires stoicism and resolve, yet the employees felt overcome. “We all just had a good cry,” Nicole Smith, Blue Mountain’s executive director, recalled.

As disheartened as Smith and her co-workers were, they also had reason to feel fortunate, at least compared with peers elsewhere. Soon after Dobbs was announced, fourteen states began enforcing sweeping new bans on abortion. Had the matter been left to the Republican Party in Montana—which holds a super-majority in the state legislature and in 2022 adopted a platform calling for a prohibition on abortion—the Blue Mountain Clinic would have encountered similar restrictions. But in 1999 the Montana Supreme Court had ruled that the right to privacy inscribed in the state constitution applied to medical judgments affecting bodily integrity, including the decision to terminate a pregnancy. This legal backstop insured that clinics like Smith’s could continue operating even if the state legislature passed regressive new laws.

Esta historia es de la edición May 15, 2023 de The New Yorker.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición May 15, 2023 de The New Yorker.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

THE FRENZY Joyce Carol Oates

Early afternoon, driving south on the Garden State Parkway with the girl beside him.

UPDATED KENNEDY CENTER 2025 SCHEDULE

April 1—A. R. Gurney’s “Love Letters,” with Lauren Boebert and Kid Rock

YOU MAD, BRO?

Young men have gone MAGA. Can the left win them back?

ONWARD AND UPWARD WITH THE ARTS BETTING ON THE FUTURE

Lucy Dacus after boygenius.

STEAL, ADAPT, BORROW

Jonathan Anderson transformed Loewe by radically reinterpreting classic garments. Is Dior next?

JUST BETWEEN US

The pleasures and pitfalls of gossip.

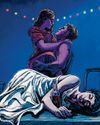

INHERIT THE PLAY

The return of “A Streetcar Named Desire” and “Ghosts.”

LEAVE WITH DESSERT

Graydon Carter’s great magazine age.

INTERIORS

The tyranny of taste in Vincenzo Latronico’s “Perfection.”

Naomi Fry on Jay McInerney's "Chloe's Scene"

As a teen-ager, long before I lived in New York, I felt the city urging me toward it. N.Y.C., with its art and money, its drugs and fashion, its misery and elation—how tough, how grimy, how scary, how glamorous! For me, one of its most potent siren calls was “Chloe’s Scene,” a piece written for this magazine, in 1994, by the novelist Jay McInerney, about the then nineteen-year-old sometime actress, sometime model, and all-around It Girl Chloë Sevigny.