GOETHE'S claim of 1787 that 'in no country has this art'-by which he meant watercolour-been brought to greater perfection than in Italy' might come as a shock to believers in the primacy of the English school. At that date, there was probably only one superlative Italian practitioner, Giovanni Battista Lusieri (17541821). However, it is arguable that had the great man said instead that nowhere had it been brought to greater perfection 'than by British and other foreign artists working in Italy', he would have been nearer the mark.

The example had been set by Claude in the 17th century and, in the second half of the 18th century, Italian light, landscapes and monuments drew together young painters and sculptors from Britain, Switzerland, Germany, France and Scandinavia in what was, effectively, an international art college. They socialised and worked with each other and their Italian counterparts, to the considerable benefit of all. Grand Tourism provided a lucrative market for topographical views that involved open-air work and watercolour was the ideal medium in which to supply them. These artists included John Robert Cozens, William Pars, Francis Towne and John 'Warwick' Smith, together with the Swiss Louis Ducros (1748-1810) and the German Jakob Philipp Hackert (1737-1807), all of whom produced their best or most interesting work in Italy.

Esta historia es de la edición August 31, 2022 de Country Life UK.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición August 31, 2022 de Country Life UK.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

Save our family farms

IT Tremains to be seen whether the Government will listen to the more than 20,000 farming people who thronged Whitehall in central London on November 19 to protest against changes to inheritance tax that could destroy countless family farms, but the impact of the good-hearted, sombre crowds was immediate and positive.

A very good dog

THE Spanish Pointer (1766–68) by Stubbs, a landmark painting in that it is the artist’s first depiction of a dog, has only been exhibited once in the 250 years since it was painted.

The great astral sneeze

Aurora Borealis, linked to celestial reindeer, firefoxes and assassinations, is one of Nature's most mesmerising, if fickle displays and has made headlines this year. Harry Pearson finds out why

'What a good boy am I'

We think of them as the stuff of childhood, but nursery rhymes such as Little Jack Horner tell tales of decidedly adult carryings-on, discovers Ian Morton

Forever a chorister

The music-and way of living-of the cabaret performer Kit Hesketh-Harvey was rooted in his upbringing as a cathedral chorister, as his sister, Sarah Sands, discovered after his death

Best of British

In this collection of short (5,000-6,000-word) pen portraits, writes the author, 'I wanted to present a number of \"Great British Commanders\" as individuals; not because I am a devotee of the \"great man, or woman, school of history\", but simply because the task is interesting.' It is, and so are Michael Clarke's choices.

Old habits die hard

Once an antique dealer, always an antique dealer, even well into retirement age, as a crop of interesting sales past and future proves

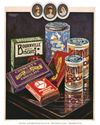

It takes the biscuit

Biscuit tins, with their whimsical shapes and delightful motifs, spark nostalgic memories of grandmother's sweet tea, but they are a remarkably recent invention. Matthew Dennison pays tribute to the ingenious Victorians who devised them

It's always darkest before the dawn

After witnessing a particularly lacklustre and insipid dawn on a leaden November day, John Lewis-Stempel takes solace in the fleeting appearance of a rare black fox and a kestrel in hot pursuit of a pipistrelle bat

Tarrying in the mulberry shade

On a visit to the Gainsborough Museum in Sudbury, Suffolk, in August, I lost my husband for half an hour and began to get nervous. Fortunately, an attendant had spotted him vanishing under the cloak of the old mulberry tree in the garden.