Intentar ORO - Gratis

Mill, Free Speech & Social Media

Philosophy Now

|August/September 2022

Nevin Chellappah asks whether John Stuart Mill's famous account of free speech is still sustainable in the age of Twitter.

It is arguably the paramount value in liberal democracies and the foundation of our other liberties. The fervent endorsement of free speech by so many today can be traced back to John Stuart Mill's reasoning in Chapter 2 of his essay On Liberty (1859). Mill made a powerful argument for allowing free speech because, he said, it is essential in the search for truth. Yet, whilst Mill had a clear conception of the end benefits of free speech, many of its modern defenders tend by contrast to see it as a prima facie good: something that should be allowed except where there is a particular reason not to. The implication is that free speech has an inherent value, not just an instrumental one, and this suggests a fundamental shift in how we understand it. Hence, in this article I will argue that the classical liberal version of free speech espoused by Mill is no longer compatible with the digital age, especially for social media.

Mill's Argument for Free Speech

First, let me set out Mill's account of free speech. His first concern in On Liberty is with the suppression of opinions by an authority. For him:

"The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error."

In response to censorship being presented as a trusted system to filter out true expressions from false ones, Mill says that there is no perfect censor. This is demonstrated by history, with past ages suppressing ideas that are now accepted to be true (the

Esta historia es de la edición August/September 2022 de Philosophy Now.

Suscríbete a Magzter GOLD para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9000 revistas y periódicos.

¿Ya eres suscriptor? Iniciar sesión

MÁS HISTORIAS DE Philosophy Now

Philosophy Now

Bilbo Theorizes About Wellbeing

Eric Comerford overhears Bilbo and Gandalf discussing happiness.

9 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

What Women?

Marcia Yudkin remembers almost choking at Cornell

11 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Islamic Philosophers On Tyranny

Amir Ali Maleki looks at tyranny from an Islamic perspective.

4 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Peter Singer

The controversial Australian philosopher defends the right to choose to die on utilitarian grounds

5 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Another Conversation with Martin Heidegger?

Raymond Tallis talks about communication problems.

7 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Letters

When inspiration strikes, don't bottle it up. Email me at rick.lewis@philosophynow.org Keep them short and keep them coming!

17 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

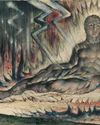

The Philosophy of William Blake

Mark Vernon looks at the imaginative thinking of an imaginative artist.

9 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Philosophical Haiku

Peering through life’s lens God in nature is deduced: The joy of being.

1 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Philosophy Shorts

More songs about Buildings and Food' was the title of a 1978 album by the rock band Talking Heads. It was about all the things rock stars normally don't sing about. Pop songs are usually about variations on the theme of love; tracks like Rose Royce's 1976 hit 'Car Wash' are the exception. Philosophers, likewise, tend to have a narrow focus on epistemology, metaphysics and trifles like the meaning of life. But occasionally great minds stray from their turf and write about other matters, for example buildings (Martin Heidegger), food (Hobbes), tomato juice (Robert Nozick), and the weather (Lucretius and Aristotle). This series of Shorts is about these unfamiliar themes; about the things philosophers also write about.

2 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Philosophy Now

Hedonic Treadmills in the Vale of Tears

Michael Gracey looks at how philosophers have pursued happiness.

8 mins

December 2025 / January 2026

Translate

Change font size