He told me this on a warm March day in a courtyard in central Kigali, almost exactly 30 years later. I had come to Rwanda because I wanted to understand how the genocide is remembered-through the country's official memorials as well as in the minds of victims.

And I wanted to know how people like Longolongo look back on what they did.

Longolongo was born in Kigali in the mid-1970s. As a teenager in the late 1980s, he didn't feel any personal hatred toward Tutsi. He had friends who were Tutsi; his own mother was Tutsi. But by the early 1990s, extremist Hutu propaganda had started to spread in newspapers and on the radio, radicalizing Rwandans. Longolongo's older brother tried to get him to join a far-right Hutu political party, but Longolongo wasn't interested in politics. He just wanted to continue his studies.

On April 6, 1994, Longolongo attended a funeral for a Tutsi man. At about 8:30 p.m., in the midst of the funeral rituals, the sky erupted in red fire and black smoke. The news traveled fast: A plane carrying the Rwandan president, Juvénal Habyarimana, and the Burundian president, Cyprien Ntaryamira, had been shot down over Kigali. No one survived.

Responsibility for the attack has never been conclusively determined. Some have speculated that Hutu extremists shot down the plane; others have blamed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a Tutsi military group that had been fighting Hutu government forces near the Ugandan border. Whoever was behind it, the event gave Hutu militants a pretext for the massacre of Tutsi.

The killing started that night.

Almost as if they had been waiting for the signal, Hutu militia members showed up in Longolongo's neighborhood. One group arrived at his home and called for his brother. When he came to the door, they gave his brother a gun and three grenades and told him to come with them.

Esta historia es de la edición November 2024 de The Atlantic.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor ? Conectar

Esta historia es de la edición November 2024 de The Atlantic.

Comience su prueba gratuita de Magzter GOLD de 7 días para acceder a miles de historias premium seleccionadas y a más de 9,000 revistas y periódicos.

Ya eres suscriptor? Conectar

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

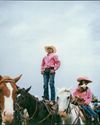

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.