For Stela Wanda Pereira da Silva, the breaking point came when her father posted a video of a woman getting assassinated to the family’s private WhatsApp group, calling it an example of the violence that would ensue if leftist Workers’ Party candidate Fernando Haddad prevailed in Brazil’s presidential election.

Da Silva, a 22-year-old resident of the coastal city of Salvador and a Haddad supporter, did some digging and discovered that the woman in the video was the victim of a robbery gone bad and not a politically motivated hit, as her father maintained. When she showed her family that the post was fake news—from Venezuela, yet—a civil war broke out, with half the group’s members defending her and the other half taking her father’s side.

“Our family was totally divided because of this election, so I had to leave the group,” says da Silva, who acknowledges that her relationship with her father has always been turbulent. Her experience on the platform isn’t unique, she says: “I have many friends who would prefer to leave their family WhatsApp group than deal with the unhealthy environment they create.”

Brazilians are among the world’s top users of social media, leaving them especially exposed to fake news and political influence campaigns online. Social media forums have replaced traditional media, which for decades were controlled largely by a single Brazilian conglomerate, Globo Group. Facebook Inc.-owned WhatsApp, in particular, has become the main vehicle for the internecine spats that happen elsewhere on Twitter or Facebook. Brazil is WhatsApp’s top market, with more than half of its 208 million people counted as users. They cluster in family or affinity groups whose typical fare is quotidian— holiday plans, an upcoming volleyball match, dinner Thursday night. But the groups also serve as virtual propulsion jets for political news, both real and fake.

“Brazil is dealing with a very powerful combination right now,” says Maurício Santoro, a political scientist at Rio de Janeiro State University. “It’s a combination of a lack of confidence in traditional media and easy access to alternative social media outlets.”

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Instagram's Founders Say It's Time for a New Social App

The rise of AI and the fall of Twitter could create opportunities for upstarts

Running in Circles

A subscription running shoe program aims to fight footwear waste

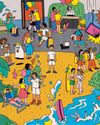

What I Learned Working at a Hawaiien Mega-Resort

Nine wild secrets from the staff at Turtle Bay, who have to manage everyone from haughty honeymooners to go-go-dancing golfers.

How Noma Will Blossom In Kyoto

The best restaurant in the world just began its second pop-up in Japan. Here's what's cooking

The Last-Mover Problem

A startup called Sennder is trying to bring an extremely tech-resistant industry into the age of apps

Tick Tock, TikTok

The US thinks the Chinese-owned social media app is a major national security risk. TikTok is running out of ways to avoid a ban

Cleaner Clothing Dye, Made From Bacteria

A UK company produces colors with less water than conventional methods and no toxic chemicals

Pumping Heat in Hamburg

The German port city plans to store hot water underground and bring it up to heat homes in the winter

Sustainability: Calamari's Climate Edge

Squid's ability to flourish in warmer waters makes it fitting for a diet for the changing environment

New Money, New Problems

In Naples, an influx of wealthy is displacing out-of-towners lower-income workers