CATEGORIES

Categories

HOW TIKTOK GREW FROM A FUN APP FOR TEENS INTO A POTENTIAL NATIONAL SECURITY THREAT

If it feels like TikTok has been around forever, that's probably because it has, at least if you're measuring via internet time. What's now in question is whether it will be around much longer and, if so, in what form?

TRUMP TO ANNOUNCE NEWLY FORMED PARTNERSHIP INVESTING $500B IN AI

President Donald Trump is announcing investments worth up to $500 billion for infrastructure tied to artificial intelligence by a new partnership formed by OpenAl, Oracle and SoftBank.

TRUMP RESCINDS BIDEN'S EXECUTIVE ORDER ON AI SAFETY IN ATTEMPT TO DIVERGE FROM HIS PREDECESSOR

Hours after returning to the White House, President Donald Trump made a symbolic mark on the future of artificial intelligence by repealing former President Joe Biden's guardrails for the fast-developing technology.

BANNING CELLPHONES IN SCHOOLS GAINS POPULARITY IN RED AND BLUE STATES

Arkansas’ Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders and California's Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom have little in common ideologically, but the two have both been vocal supporters of an idea that’s been rapidly gaining bipartisan ground in the states: Students’ cellphones need to be banned during the school day.

LEWIS HAMILTON ARRIVES IN MARANELLO FOR HIS 1ST DAY AT FERRARI

Seven-time Formula 1 champion Lewis Hamilton arrived at Ferrari's headquarters this week to get down to work with his new team.

'ONCE IN A LIFETIME' SNOW HITS PARTS OF THE U.S. SOUTH

A winter storm sweeping through the U.S. South on Tuesday was dumping snow at levels millions of residents haven't seen before.

WHAT'S NEXT FOR EVS UNDER PRESIDENT TRUMP?

President Donald Trump signed an executive order promising to eliminate what he incorrectly labels “the electric vehicle mandate” imposed under former President Joe Biden. His order on Monday is consistent with pledges Trump made on the campaign trail to end what he calls a “preposterous” focus on EVs by Biden and other Democrats.

NETFLIX'S BET ON LIVE EVENTS HELPED REEL IN 19 MILLION MORE SUBSCRIBERS IN HOLIDAY-SEASON QUARTER

Netflix added nearly 19 million subscribers during the holiday-season quarter to help propel its earnings beyond analysts' projections, capping the video streaming service's best year yet in a sign that its expansion into live programming is paying off.

UK WATCHDOG TARGETS APPLE, GOOGLE MOBILE ECOSYSTEMS WITH NEW DIGITAL MARKET POWERS

Google's Android and Apple's iOS are facing fresh scrutiny from Britain's competition watchdog, which announced investigations Thursday targeting the two tech giants' mobile phone ecosystems under new powers to crack down on digital market abuses.

TIPS ON OVERCOMING THE LOSS OF CHERISHED. PERSONAL BELONGINGS IN DISASTERS

Losing important sentimental belongings—those items that represented who you are—can be traumatic for those who go through disasters that destroy homes. Some tips on how to get through it, emotionally and practically:

Evolution - SHAPING THE NEXT WAVE OF APPLE TECHNOLOGY IN 2025

Apple faces a pivotal year in 2025, balancing innovation with market pressures. Efforts in mixed reality, Apple’s generative Al project, the company’s 2030 carbon-neutral pledge, and growth in its services division with platforms like TV+ will all play a role in elevating the firm.

TRUMP, A POPULIST PRESIDENT, IS FLANKED BY TECH BILLIONAIRES AT HIS INAUGURATION

Some of the most exclusive seats at President Donald Trump's inauguration on Monday were reserved for powerful tech CEOs who also happen to be among the world’s richest men.

HOW SCIENTISTS WITH DISABILITIES ARE MAKING RESEARCH LABS AND FIELDWORK MORE ACCESSIBLE

The path to Lost Lake was steep and unpaved, ou lined with sharp rocks and holes.

GOVERNOR PROPOSES BANNING CELLPHONES IN SCHOOLS THROUGHOUT NEW YORK STATE STARTING NEXT FALL

Students throughout New York state might have to give up their cellphones during school hours starting next fall under a proposal announced Tuesday by Gov. Kathy Hochul.

MUSK CLASHES WITH OPENAI CEO SAM ALTMAN OVER TRUMP-SUPPORTED STARGATE AI DATA CENTER PROJECT

Elon Musk is clashing with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman over the Stargate artificial intelligence infrastructure project touted by President Donald Trump, the latest in a feud between the two tech billionaires that started on OpenAl's board and is now testing Musk's influence with the new president.

TESLA RECEIVES MORE THAN 100K MODEL Y JUNIPER ORDERS IN LESS THAN 2 WEEKS, STARTS PRODUCTION AT GIGA BERLIN AFTER SHANGHAI

Tesla (TSLA) has received over 100,000 orders for the new design-refreshed 2025 Tesla Model Y Juniper in just two weeks following its launch in key markets like China, Asia, Australia, and New Zealand. This overwhelming demand showcases Tesla's strong foothold in the global EV market and the immense popularity of its latest Model Y update.

AI EXPERIMENT IN HALFPIPE JUDGING AT X GAMES WILL GIVE SNOWBOARDERS A GLIMPSE INTO THE FUTURE

The X Games will experiment judging halfpipe runs this week in Aspen using artificial intelligence, the cutting-edge technology that could someday play a role in the way subjectively judged sports are scored.

SAMSUNG AIMS TO TURN ITS NEXT GENERATION OF GALAXY SMARTPHONES INTO AI COMPANIONS

Samsung is injecting another dose of artificial intelligence into its next lineup of Galaxy smartphones, escalating an effort to simplify people's lives while deepening their dependence on a device that accompanies them almost everywhere.

YOUR MONEY: 5 IDEAS FOR AVOIDING AN OVEREMPHASIS ON SHORT-TERM RESULTS

Recency bias is the tendency to place too much weight on the latest performance trends while giving short shrift to other factors, such as fundamentals, valuation, or long-term market averages.

SNOOTY MOORE SCARES OFF THE GUYS!

DETERMINED Demi Moore was the talk of the Golden Globes for her snotty attitude toward Kylie Jenner, and sources dish she's equally full of herself when it comes to dating these days - and the lousy attitude is why the 62-year-old actress has had such poor luck snaring suitors! \"She's got an edge and she's intimidating to guys, plus she's a bit of a control freak and her dogs and daughters always come first,\" spills an insider.

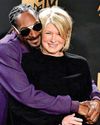

SNOOP DOGG HOUNDED TO DROP MARTHA!

His wife's had enough of domestic diva rival

DENISE ON HOOK FOR HUBBY'S MONEY MESS!

DRAMA magnet Denise Richards' dough may be in jeopardy as her wellness guru husband is being sued by a creditor and grappling with a fraud lawsuit that charges he refused a promised refund to a woman with terminal cancer, sources spill.

PRINCE WILLIAM'S PORNO PALACE!

PERVY Prince William’s secret penchant for porn is rocking an already rattled monarchy — and chatter about his horny habit is embarrassing the future king’s cancer-survivor wife, Kate, courtiers confide.

MUNIZ MOPES OVER MALCOLM REBOOT!

FORMER TV tyke Frankie Muniz was excited about doing a reboot of his hit series Malcolm in the Middle, but his cryptic social media comment on friendship — or the lack thereof — seems to suggest it's not going so well!

VULNERABLE VANNA PUSHES BEAU AWAY!

Gun-shy about pulling trigger on marriage

CHER NEEDS TO DITCH COUGAR ACT

She just can't turn back time with boytoy

ROCKY ROAD TO ROMANCE!

Two child stars from the 2003 hit School of Rock have tied the knot — even though they were NOT interested in making beautiful music together 22 years ago while filming the Jack Black movie!

PASSION RULES PARIS!

King of Pop daughter ready to skip prenup

Hugh Jackman & Sutton Foster What They Sacrificed for LOVE

THE MUSIC MAN CO-STARS HAVE ENDURED PAINFUL CHANGES IN THEIR LIVES TO BE TOGETHER

WHO KILLED Thelma Todd?

THE FILM COMEDIENNE TURNED RESTAURATEUR DIED AT AGE 29 UNDER SUSPICIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES