MR. PRESIDENT

Its candidate won every presidential election beginning in 1800. No elections had been very close. But those easy victories hid disagreements within the party.

Four Democratic-Republican candidates decided to run for president in 1824. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts and two others—Speaker of the House of Representatives Henry Clay of Kentucky and Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford of Georgia—were well-educated gentlemen. They had the backing of wealthy farmers, businessmen, and other upper-class people. Such support had been enough to win earlier elections.

Prior to 1824, the electorate had been made up of wealthy, property-owning white men. But in 1824, ordinary white American men began voting. Most of those voters supported the fourth Democratic-Republican candidate: General Andrew Jackson. Jackson was different from the other three men. Born in rural South Carolina to poor parents, he was self-educated. He promised to give less-privileged Americans a voice in government.

Jackson’s message was well received. In the general election, he won more popular votes than any other candidate. He also took first place in the Electoral College. But he did not win a majority of electoral votes. So, as stated in the 12th Amendment, the decision of whom to select as the next president moved to the U.S. House of Representatives. Only the top three vote-getters were eligible.

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,500+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

nellie Bly Journalist

nellie Bly's first newspaper articles appeared in print when she was just 20 years old.

Arabella Mansfield -Lawyer

Arabella Mansfield started out life as Belle Babb (1846-1911). She grew up in a Midwest family that valued education. In 1850, her father left to search for gold in California. He died in a tunnel accident a few years later.

Sarah Josepha Hale Editor

Long before Vogue or Glamour caught women's attention, Godey's Lady's Book introduced the latest fashions.

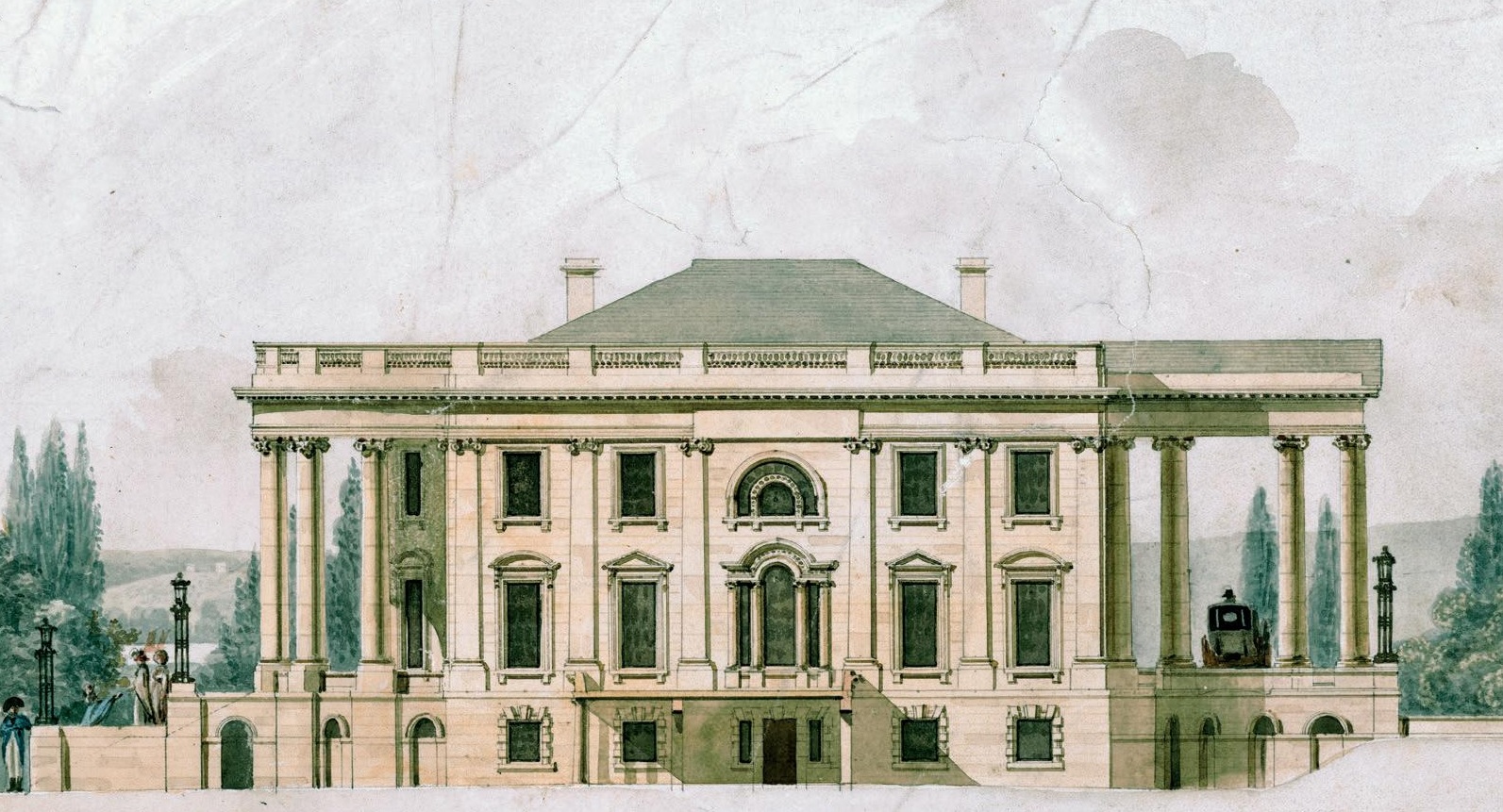

Louise Blanchard Bethune - Architect

Louise Blanchard Bethune (1856-1915) showed early promise in math. Lucky for her, her father was the principal and a mathematics teacher in a school in Waterloo, New York. Instead of going to school, Louise's father taught her at home until she was 11 years old. She also discovered a skill for planning houses. It developed into a lifelong interest in architecture and a place in history as the first professional female architect in the United States.

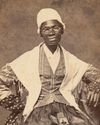

Sojourner Truth Speaker

There was a time when slavery wastes abolished the institution over a number of decades. New York abolished slavery in 1827. Isabella Baumfree (c. 1797-1883) was born enslaved in Hurley, New York. When she was nine, she was taken from her parents and sold. She then was sold several more times. Some of her owners were cruel and abused her. During that time, she had several children.

Getting Started

In this editorial cartoon, a young 19th-century woman must overcome the obstacle of carrying a heavy burden while climbing a multirung ladder before she can achieve \"Equal Suffrage.\"

Leonora M. Barry - Investigator

When Leonora M. Barry (1849-1923) was a young girl, her family left Ireland to escape a famine. They settled in New York. Barry became a teacher. In 1872, she married a fellow Irish immigrant. At that time, married women were not allowed to work. So, Barry stayed home to raise their three children.

Finding a New Path

For many Americans, this month's mystery hero represents the ultimate modern trailblazer. She is recognized by just her first name.

The Grimké Sisters Abolitionists

Every night, Dinah was supposed to brush the E hair of her mistress, Sarah Moore Grimké (1792-1873). But one night, 12-year-old Sarah stopped Dinah. She wanted to help Dinah instead. They had to be quiet so they wouldn't get caught. It was 1804 in Charleston, South Carolina. The Grimkés were among Charleston's major slaveholding families. Strict laws regulated the behavior of both master and enslaved people.

Frances Willard Leader

During Frances Willard's lifetime (1839-1898), she was the best-known woman in America: She headed the largest women's organization in the worldthe Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). In that role, her abilities shone as a social activist, a dynamic speaker, and a brilliant organizer. She educated women on how to run meetings, write petitions, give speeches, and lobby state and federal legislators.