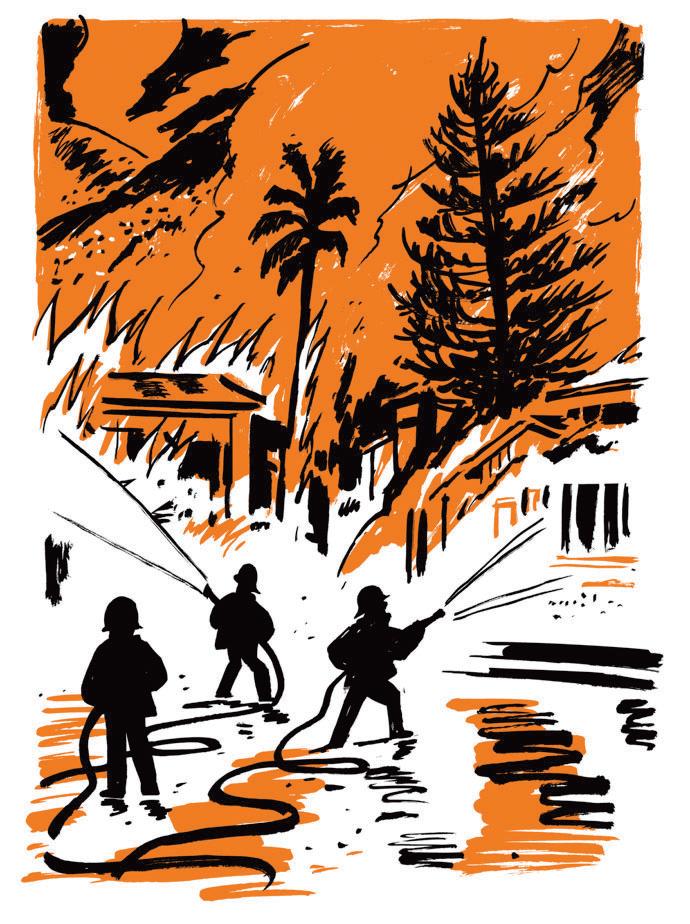

By the time the Los Angeles Fire Department had succeeded in putting out the blaze, more than six thousand acres had been scorched and nearly five hundred houses had been destroyed, including ones belonging to Zsa Zsa Gabor and Aldous Huxley.

Faulted for its part in the disaster, the L.A.F.D. turned to Hollywood. In 1962, it released a movie, narrated by the actor William Conrad, aimed at answering its critics. Part instructional video, part film noir, the movie opened with the sound of whistling wind and a shot of rustling vegetation. When the Santa Ana winds blow, Conrad intoned, channelling Raymond Chandler, the "atmosphere grows tense, oppressive. People tire easily, argue more. Even the suicide rate rises." According to the film, the L.A.F.D. had known that danger was coming and had positioned crews around the city. As the flames raced through the brush, the chief engineer ordered "everything available into the fire." But "everything was not enough." The streets became clogged with people trying to escape by car and on foot. Then the water ran out.

How had the situation got so out of control, the movie asked. The answer lay in precisely those qualities that made L.A. such an attractive place to live: its climate, its canyonside homes, its wild ridges accessible only by narrow roads.

The whole arrangement was a "design for disaster," which was also the name the L.A.F.D. gave to the film. "These are the odds," Conrad said, in closing.

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

THE FRENZY Joyce Carol Oates

Early afternoon, driving south on the Garden State Parkway with the girl beside him.

UPDATED KENNEDY CENTER 2025 SCHEDULE

April 1—A. R. Gurney’s “Love Letters,” with Lauren Boebert and Kid Rock

YOU MAD, BRO?

Young men have gone MAGA. Can the left win them back?

ONWARD AND UPWARD WITH THE ARTS BETTING ON THE FUTURE

Lucy Dacus after boygenius.

STEAL, ADAPT, BORROW

Jonathan Anderson transformed Loewe by radically reinterpreting classic garments. Is Dior next?

JUST BETWEEN US

The pleasures and pitfalls of gossip.

INHERIT THE PLAY

The return of “A Streetcar Named Desire” and “Ghosts.”

LEAVE WITH DESSERT

Graydon Carter’s great magazine age.

INTERIORS

The tyranny of taste in Vincenzo Latronico’s “Perfection.”

Naomi Fry on Jay McInerney's "Chloe's Scene"

As a teen-ager, long before I lived in New York, I felt the city urging me toward it. N.Y.C., with its art and money, its drugs and fashion, its misery and elation—how tough, how grimy, how scary, how glamorous! For me, one of its most potent siren calls was “Chloe’s Scene,” a piece written for this magazine, in 1994, by the novelist Jay McInerney, about the then nineteen-year-old sometime actress, sometime model, and all-around It Girl Chloë Sevigny.