Around the Georgian village of Khurvaleti, Russia’s occupation can creep forward a few yards at night. It often starts with a line ploughed across a field. Then a green sign will materialise, warning people not to cross. Then the concertina wire appears.

Khurvaleti is at the southern edge of South Ossetia, a breakaway region occupied by Russian troops since a five-day war with Georgia in 2008, in what proved to be a dress rehearsal for Ukraine.

There are few soldiers to be seen in the two military bases in the hills on either side of Khurvaleti. But Georgians fear that if Russia were to prevail in Ukraine, Putin’s forces would be back. For now, the line marking the extent of Russian occupation is watched by EU monitors looking for new signs of “borderisation”.

“Usually it starts with soft borderisation – ditches, ribbons on trees that show demarcation between the two sites,” said Klaas Maes, a spokesperson for the monitoring mission. “The ditches become fences, the fences become barbed wire, then the wire is fortified with extra watchtowers.”

Five years ago, villagers woke to find Khurvaleti had been cut in two by a wire fence; later, a watchtower was built to guard the barrier. Villagers were separated from family, friends and their land. A dividing line demarcated by a fence is enforced by fines and sometimes lengthy jail sentences. The nearest crossing point is 50km away and open 10 days a month.

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

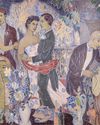

Finn family murals

The optimism that runs through Finnish artist Tove Jansson's Moomin stories also appears in her public works, now on show in a Helsinki exhibition

I hoped Finland would be a progressive dream.I've had to think again Mike Watson

Oulu is five hours north from Helsinki by train and a good deal colder and darker each winter than the Finnish capital. From November to March its 220,000 residents are lucky to see daylight for a couple of hours a day and temperatures can reach the minus 30s. However, this is not the reason I sense a darkening of the Finnish dream that brought me here six years ago.

A surplus of billionaires is destabilising our democracies Zoe Williams

The concept of \"elite overproduction\" was developed by social scientist Peter Turchin around the turn of this century to describe something specific: too many rich people for not enough rich-person jobs.

'What will people think? I don't care any more'

At 90, Alan Bennett has written a sex-fuelled novella set in a home for the elderly. He talks about mourning Maggie Smith, turning down a knighthood and what he makes of the new UK prime minister

I see you

What happens when people with acute psychosis meet the voices in their heads? A new clinical trial reveals some surprising results

Rumbled How Ali ran rings around apartheid, 50 years ago

Fifty years ago, in a corner of white South Africa, Muhammad Ali already seemed a miracle-maker.

Trudeau faces 'iceberg revolt'as calls grow for PM to quit

Justin Trudeau, who promised “sunny ways” as he won an election on a wave of public fatigue with an incumbent Conservative government, is now facing his darkest and most uncertain political moment as he attempts to defy the odds to win a rare fourth term.

Lost Maya city revealed through laser mapping

After swapping machetes and binoculars for computer screens and laser mapping, a team of researchers have discovered a lost Maya city containing temple pyramids, enclosed plazas and a reservoir which had been hidden for centuries by the Mexican jungle.

'A civil war' Gangs step up assault on capital

Armed fighters advance into neighbourhoods at the heart of Port-au-Prince as authorities try to restore order

Reality bites in the Himalayan 'kingdom of happiness'

High emigration and youth unemployment levels belie the mountain nation's global reputation for cheeriness