Take us back, little time machine, with your bleepings and your flashings; take us back to crusty old London in the late 1650s, so we can clap the electrodes onto the sleeping head of blind John Milton. Let’s monitor the activity in the poet’s brain. Let’s observe its nocturnal waves. And let’s pay particular attention as his sightless eyes begin to flick and roll in deepest, darkest, dream-friendliest REM sleep, because it is at this point (we presume) that the spirit whom he calls Urania, a nightly visitor with a perfect—not to say Miltonic— command of blank verse, will manifest before his un conscious mind and give him the next 40 lines of Paradise Lost.

Is that really how it happened? Is it possible that the most monumental and cosmically scaled poem in the English language, nearly 11,000 lines of war in heaven, snakes in the garden, and the slamming of the gates behind Adam and Eve, was dictated by a voice in a dream? Did Milton—to put it another way—write Paradise Lost in his sleep? We’ve got only his word for it, of course, although it appears to be a fact that he arose each morning with lines of verse fully formed and ready for transcription. (For this task Milton seems to have availed himself of whoever happened to be around—to have “employed any casual visitor in disburthening his memory,” as Dr. Johnson wrote in his short biography.) Another fact: If he tried composing later in the day, he’d have no luck.

この記事は The Atlantic の January - February 2022 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,000 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です ? サインイン

この記事は The Atlantic の January - February 2022 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,000 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です? サインイン

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

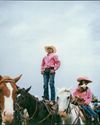

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.