On a tooth-cleaning visit not long ago, Barbara told me that in the late 1970s, when she attended dental school, her professors expected that most middle- class patients would lose a lot of their teeth and need dentures by the time they were in their 60s. Today, she said, most middle- class people keep their teeth until they are 80. The main reason for this, Barbara explained, was fluoridation— the practice of putting fluoride compounds in community drinking water to combat tooth decay.

For reasons I can’t now recall, I mentioned this remark on social media. The inevitable but somehow surprising response: People I did not know troubled themselves to tell me that I was an idiot, and that fluoridation was terrible. Their skepticism made an impression. I found myself staring suspiciously, as I brushed, at my Colgate toothpaste. STRENGTHENS TEETH WITH ACTIVE FLUORIDE, the label promised. A thought popped into my head: I am now rubbing fluoride directly onto my teeth. So why is my town also dumping it into my drinking water?

Surely applying Colgate’s meticulously packaged fluoride paste directly onto my teeth, where it bonds with the surface to create a protective layer, was better than the more indirect method of pouring fluoride into reservoirs so that people drinking the water can absorb the fluoride, some of which then makes its way into their saliva.

この記事は The Atlantic の April 2020 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,000 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です ? サインイン

この記事は The Atlantic の April 2020 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,000 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です? サインイン

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

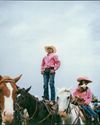

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.