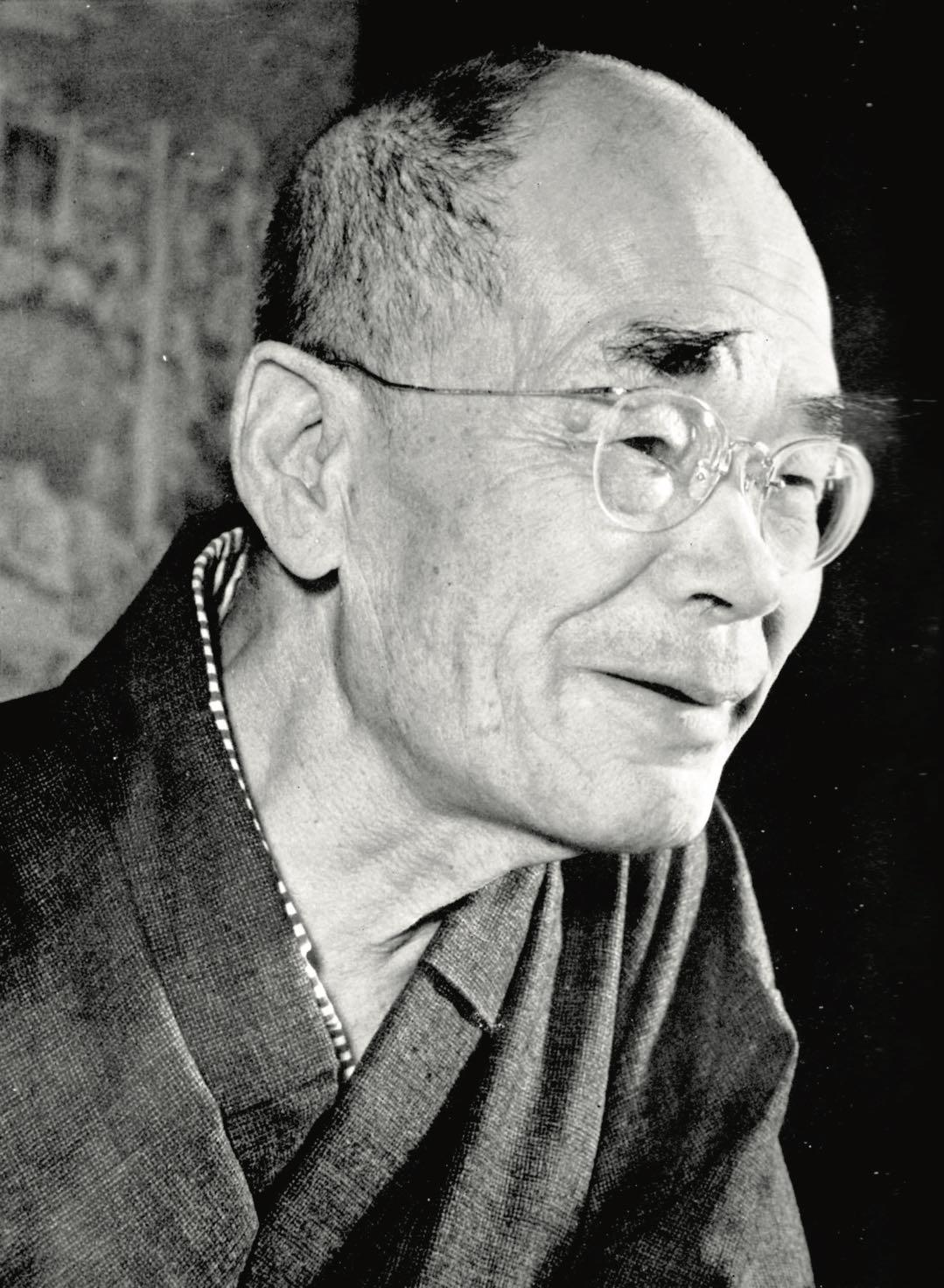

Daisetsu Suzuki (1870-1966)

According to Christmas Humphreys, the founder in 1924 of the Buddhist Society in London, Zen Buddhism is the 'apotheosis' - the divine culmination - of Buddhism. Humphreys on to describe Zen as a practical, non-intellectual method of directly experiencing 'ultimate reality'. If so, then Zen should be of interest to phenomenologists, Kantians and all the other Western philosophers who have argued about our ability to apprehend reality. But was he right? Humphreys derived most of his ideas about Zen from his friend, the Japanese scholar Daisetsu T. Suzuki (1870-1966), who has been well described as the man who brought Zen to the West.

Perhaps the best-known Japanese philosopher of the twentieth century, Suzuki was born into a Samurai family in Northern Japan in 1870. After a brief period studying at what is now Waseda University in Tokyo, Suzuki became a disciple of Zen master Shaku Soen (1859-1919), and spent five years undergoing Rinzai Zen training at the famous Engakuji Monastery in Kamakura. He is said to have become enlightened in 1895.

In 1893 Suzuki accompanied Shaku Soen to the renowned World Parliament of Religions held in Chicago. Four years later he was invited to the United States to work as a translator for the philosopher and publisher Paul Carus. What is of interest is that Carus had been a student of Schopenhauer, whose ethics features many Buddhist ideas, and was also an early advocate of panpsychism (which means 'mind everywhere'), which is currently fashionable in academic philosophy of mind.

Suzuki spent eleven years in the United States, between 1897-1908, and developed a deep interest in Western philosophy, Christian mysticism, and comparative religion. He came to write important studies of the German Neoplatonist Meister Eckhart, and the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, emphasizing the close affinities between Christian mysticism and Mahayana Buddhism (of which Zen is a branch).

この記事は Philosophy Now の August/September 2022 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,500 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です ? サインイン

この記事は Philosophy Now の August/September 2022 版に掲載されています。

7 日間の Magzter GOLD 無料トライアルを開始して、何千もの厳選されたプレミアム ストーリー、9,500 以上の雑誌や新聞にアクセスしてください。

すでに購読者です? サインイン

Affirmative Action for Androids

Jimmy Alfonso Licon asks, when should we prioritise android rights?

Welcome to the Civilization of the Liar's Paradox

Slavoj Žižek uncovers political paradoxes of lying.

The Importance of the Purple

Massimo Pigliucci looks for threads of integrity in a morally compromised world.

Ethics for the Age of AI

Mahmoud Khatami asks, can machines make good moral decisions?

Anand Vaidya (1976-2024)

Manjula Menon on the short but full career of a 'disciplinary trespasser'.

Studying Smarter with AI?

Max Gottschlich on sense and nonsense when using AI in academia.

Excusing God

Raymond Tallis highlights the problem of evil.

Stephen Fry

Perhaps unshockingly for someone who is an actor, broadcaster, comedian, director, narrator and writer, Stephen Fry has a deep interest in words and how we use them. After hearing him lecture on that subject, Marcel Steinbauer-Lewis asked him about Artificial Intelligence and how it connects with the extraordinary lure of language.

Is VR Meaningful Escapism?

Amir Haj-Bolouri enquires into possible meaning through technology.

What Simone de Beauvoir Got — And Didn't Get – About Motherhood

Nura Hossainzadeh argues that motherhood is both physical and transcendent.