In the age of index funds and private companies, even a boom can feel blah.

To the extent anyone on Wall Street cares—and many will tell you they don’t—records in stocks are good for one thing: advertising. Talk all you want about rates of return or piling it up for retirement, but nothing beats a headline about an all-time high for bringing customers in the door.

And in they have come. Cheered by what’s become by some measures the longest bull market on record, U.S. investors have plowed money into U.S. stock exchange-traded funds at a rate of almost $12 billion a month since the start of 2017, five times as much as seven years ago. There are signs of stress—like the recent sell-off in Asia—but so far they appear in U.S. investors’ peripheral vision. Anyone buying stock in an American company right now must be comfortable paying two or three times annual sales per share, a level of shareholder generosity that hasn’t been seen since the dying throes of the dot-com bubble.

When we tell our grandchildren about this bull market, we’ll start by describing its demise, in the crash of 2019, or 2020, or 2025. But we don’t know the end of this story yet. What will we say of the rest? That dips were bought and passive investing ruled, perhaps, and that a handful of tech megacaps—most of them decades old—grew to planetary size. But if the decade is remembered for anything, it could also be as the era when equities returned close to 20 percent a year on average from the March 2009 bottom and the stock market, somehow, got boring.

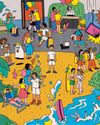

Which is to say, this isn’t the like the boom of the late 1990s. Rarely do companies have initial public offerings where their stocks double on the first day of trading. The tip-dispensing cabbies of the bubble era are driving Ubers now, and any money they have to invest is going into ETFs, not individual stocks.

Denne historien er fra September 17, 2018-utgaven av Bloomberg Businessweek.

Start din 7-dagers gratis prøveperiode på Magzter GOLD for å få tilgang til tusenvis av utvalgte premiumhistorier og 9000+ magasiner og aviser.

Allerede abonnent ? Logg på

Denne historien er fra September 17, 2018-utgaven av Bloomberg Businessweek.

Start din 7-dagers gratis prøveperiode på Magzter GOLD for å få tilgang til tusenvis av utvalgte premiumhistorier og 9000+ magasiner og aviser.

Allerede abonnent? Logg på

Instagram's Founders Say It's Time for a New Social App

The rise of AI and the fall of Twitter could create opportunities for upstarts

Running in Circles

A subscription running shoe program aims to fight footwear waste

What I Learned Working at a Hawaiien Mega-Resort

Nine wild secrets from the staff at Turtle Bay, who have to manage everyone from haughty honeymooners to go-go-dancing golfers.

How Noma Will Blossom In Kyoto

The best restaurant in the world just began its second pop-up in Japan. Here's what's cooking

The Last-Mover Problem

A startup called Sennder is trying to bring an extremely tech-resistant industry into the age of apps

Tick Tock, TikTok

The US thinks the Chinese-owned social media app is a major national security risk. TikTok is running out of ways to avoid a ban

Cleaner Clothing Dye, Made From Bacteria

A UK company produces colors with less water than conventional methods and no toxic chemicals

Pumping Heat in Hamburg

The German port city plans to store hot water underground and bring it up to heat homes in the winter

Sustainability: Calamari's Climate Edge

Squid's ability to flourish in warmer waters makes it fitting for a diet for the changing environment

New Money, New Problems

In Naples, an influx of wealthy is displacing out-of-towners lower-income workers