The next Bond movie should be called Libido of Secrecy. It should be called Marmalizer, Mercuryface, Die to Tell the Tale.

Actually—and I’m quite serious—it should be called The Black Daffodil, after Ian Fleming’s only book of poetry. Nicholas Shakespeare, in his walloping new biography, Ian Fleming: The Complete Man, describes this slim volume, bound in black and self-published in 1928, as “the holy grail for Fleming collectors.” He was 20. He was arty. Shakespeare includes a contemporary sample from Fleming’s journal: “If the wages of sin are Death / I am willing to pay / I have had my short spasm of life / now let death take its sway.” We have to rely on the sample, because The Black Daffodil itself is gone. “He read me several poems,” Fleming’s friend and sometime business partner Ivar Bryce remembered, “the beauty of which moved me deeply.” But then something went wrong, or some other presence moved in. “He took every copy that had been printed,” Bryce continued, “and consigned the whole edition pitilessly to the flames.”

Rather Bondlike, that “pitilessly.” Bondlike, too, is the “short spasm of life” in the little poem. In fact, although he wouldn’t be born for another 24 years, if you squint at the Black Daffodil episode, at this tiny debacle in the artistic life of Ian Fleming, you can indeed make out the wriggling germ of James Bond.

Denne historien er fra March 2024-utgaven av The Atlantic.

Start din 7-dagers gratis prøveperiode på Magzter GOLD for å få tilgang til tusenvis av utvalgte premiumhistorier og 9000+ magasiner og aviser.

Allerede abonnent ? Logg på

Denne historien er fra March 2024-utgaven av The Atlantic.

Start din 7-dagers gratis prøveperiode på Magzter GOLD for å få tilgang til tusenvis av utvalgte premiumhistorier og 9000+ magasiner og aviser.

Allerede abonnent? Logg på

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

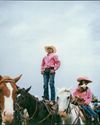

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.