THE story of modern British art is almost inextricably entwined with the two World Wars in which most of its leading names served as combatants or war artists, but Michael Ayrton was the odd man out. Within weeks of his call-up in 1941, the young RAF recruit was writing home in despair: ‘I think they are going to try and train me… and I think they are going to take my stick away from me. It will all do no good, but what can I do?’

Ayrton had had a slight limp since contracting osteomyelitis in childhood and stylish walking sticks were part of his persona. Plagued by ill health throughout his life, he was plainly not army material and—although suspected by the medical officer of having ‘definite reasons for desiring to be unfit for service’—he was eventually discharged.

One of Ayrton’s ‘definite reasons’ was that he was itching to get on with an exciting commission to design sets for a production of Macbeth directed by John Gielgud; another was his awareness that he was essentially untrainable. His dogged independence of mind had made him almost as unsuited to art school as to the army; what he learned about drawing, he basically taught himself in his teens by copying early German Renaissance masters in the Albertina when staying with an elderly cousin in Vienna.

Ayrton’s dogged independence of mind made him almost as unsuited to art school as to the army

This story is from the May 12, 2021 edition of Country Life UK.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the May 12, 2021 edition of Country Life UK.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Save our family farms

IT Tremains to be seen whether the Government will listen to the more than 20,000 farming people who thronged Whitehall in central London on November 19 to protest against changes to inheritance tax that could destroy countless family farms, but the impact of the good-hearted, sombre crowds was immediate and positive.

A very good dog

THE Spanish Pointer (1766–68) by Stubbs, a landmark painting in that it is the artist’s first depiction of a dog, has only been exhibited once in the 250 years since it was painted.

The great astral sneeze

Aurora Borealis, linked to celestial reindeer, firefoxes and assassinations, is one of Nature's most mesmerising, if fickle displays and has made headlines this year. Harry Pearson finds out why

'What a good boy am I'

We think of them as the stuff of childhood, but nursery rhymes such as Little Jack Horner tell tales of decidedly adult carryings-on, discovers Ian Morton

Forever a chorister

The music-and way of living-of the cabaret performer Kit Hesketh-Harvey was rooted in his upbringing as a cathedral chorister, as his sister, Sarah Sands, discovered after his death

Best of British

In this collection of short (5,000-6,000-word) pen portraits, writes the author, 'I wanted to present a number of \"Great British Commanders\" as individuals; not because I am a devotee of the \"great man, or woman, school of history\", but simply because the task is interesting.' It is, and so are Michael Clarke's choices.

Old habits die hard

Once an antique dealer, always an antique dealer, even well into retirement age, as a crop of interesting sales past and future proves

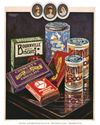

It takes the biscuit

Biscuit tins, with their whimsical shapes and delightful motifs, spark nostalgic memories of grandmother's sweet tea, but they are a remarkably recent invention. Matthew Dennison pays tribute to the ingenious Victorians who devised them

It's always darkest before the dawn

After witnessing a particularly lacklustre and insipid dawn on a leaden November day, John Lewis-Stempel takes solace in the fleeting appearance of a rare black fox and a kestrel in hot pursuit of a pipistrelle bat

Tarrying in the mulberry shade

On a visit to the Gainsborough Museum in Sudbury, Suffolk, in August, I lost my husband for half an hour and began to get nervous. Fortunately, an attendant had spotted him vanishing under the cloak of the old mulberry tree in the garden.