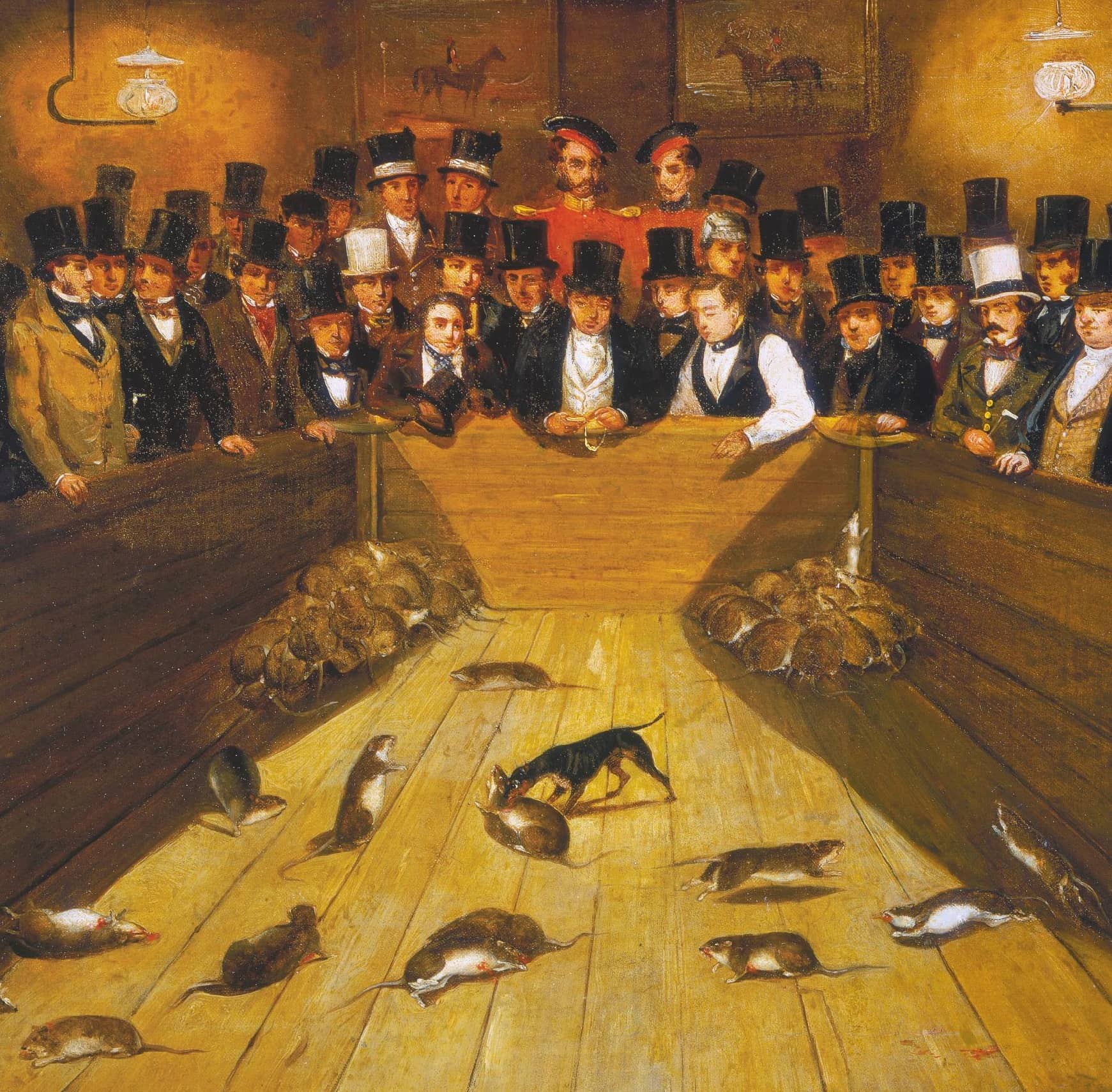

RATS scuttle across the wooden platform, watched by a crowd wearing top hats and cravats. One gentleman peers at a pocket watch as a black-and-tan English toy terrier tears through the enclosure, dispatching rodents left, right and centre. The dog is Tiny the Wonder, a Victorian celebrity that could kill 200 rats an hour in London’s baiting pits. It’s a potentially gruesome scene for a museum exhibit, but the life-sized version of the mid-19thcentury painting Rat-Catching at the Blue Anchor Tavern, Bunhill Row, Finsbury merely hints at the reality.

The rats are digital projections; the gambling men safely two-dimensional. Tiny, so small that he wore a ladies’ bracelet instead of a collar, looms larger in our imagination. The watered-down approach is entirely appropriate, because the display is part of ‘Beasts of London’, a special series of immersive installations at the Museum of London, created in partnership with the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, to tell the history of the capital through its animal tales (or tails).

The indifference towards rats in the city was understandable. They were previously thought to have caused London’s devastating plague, although, as the exhibition discusses, we now know that the spread of disease was down to another animal: the flea. However, the animals used in rat baiting weren’t always London rats; many organisers favoured stronger specimens found in the neighbouring countryside. In time, rat baiting —to be distinguished from ratting, the legal useof dogs for pest control in an unconfined space—was considered cruel. Society’s changing views on animals offer a window into a broader understanding of history.

This story is from the October 9, 2019 edition of Country Life UK.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the October 9, 2019 edition of Country Life UK.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Give it some stick

Galloping through the imagination, competitive hobby-horsing is a gymnastic sport on the rise in Britain, discovers Sybilla Hart

Paper escapes

Steven King selects his best travel books of 2024

For love, not money

This year may have marked the end of brag-art’, bought merely to show off one’s wealth. It’s time for a return to looking for connoisseurship, beauty and taste

Mary I: more bruised than bloody

Cast as a sanguinary tyrant, our first Queen Regnant may not deserve her brutal reputation, believes Geoffrey Munn

A love supreme

Art brought together 19th-century Norwich couple Joseph and Emily Stannard, who shared a passion for painting, but their destiny would be dramatically different

Private views

One of the best ways-often the only way-to visit the finest privately owned gardens in the country is by joining an exclusive tour. Non Morris does exactly that

Shhhhhh...

THERE is great delight to be had poring over the front pages of COUNTRY LIFE each week, dreaming of what life would be like in a Scottish castle (so reasonably priced, but do bear in mind the midges) or a townhouse in London’s Eaton Square (worth a king’s ransom, but, oh dear, the traffic) or perhaps that cottage in the Cotswolds (if you don’t mind standing next to Hollywood A-listers in the queue at Daylesford). The estate agent’s particulars will give you details of acreage, proximity to schools and railway stations, but never—no, never—an indication of noise levels.

Mission impossible

Rubble and ruin were all that remained of the early-19th-century Villa Frere and its gardens, planted by the English diplomat John Hookham Frere, until a group of dedicated volunteers came to its rescue. Josephine Tyndale-Biscoe tells the story

When a perfect storm hits

Weather, wars, elections and financial uncertainty all conspired against high-end house sales this year, but there were still some spectacular deals

Give the dog a bone

Man's best friend still needs to eat like its Lupus forebears, believes Jonathan Self, when it's not guarding food, greeting us or destroying our upholstery, of course