In China, history long occupied a quasi-religious status. During imperial times, dating back thousands of years and enduring until the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911, historians’ dedication to recording the truth was viewed as a check against wrongdoing by the emperor. Rulers, though forbidden from interfering, of course tried.

So have their successors. Among the most intent on harnessing history for political gain are the current leaders of the Chinese Communist Party. They routinely scrub Chinese-language scholarly books, journals, and textbooks of anything that might undermine their own legitimacy— including anything that tarnishes Mao Zedong, the founding father of the party. The effort, no small task, has not gone unchallenged. A web of amateur historians has been collecting documents and eyewitness testimony from the seven decades that have elapsed since the establishment of modern China in 1949. Guo Jian, an English professor at the University of Wisconsin at Whitewater who has translated some of their findings, describes the tenacious researchers as “the inheritors of China’s great legacy,” dedicated to “preserving memory against repression and amnesia.’’

This story is from the January - February 2021 edition of The Atlantic.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the January - February 2021 edition of The Atlantic.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

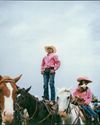

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.