Glorified for its creative benefits, the pastime has become yet another goal-driven pursuit.

Life Span, a maker of fitness equipment, claims that a treadmill desk will boost my creativity. The company’s website, where I can purchase its basic model for $1,099, features an inspirational quote from Nietzsche: “All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.” Researchers agree on the connection between an acute mind and legs in motion. Studies have shown that we do better on tests of memory and attention during or after exercise. Studies have also shown that a walker’s mental meandering is unusually conducive to innovation. “Above all, do not lose your desire to walk,” Søren Kierkegaard advised, and I’m hardly the only writer who has heeded the call, putting one foot before the other in search of fresh insights and breakthroughs in knotty arguments.

Before the advent of scientific evidence and philosophical guidance on the subject, literary odes to the creative and health benefits of walking flourished. No one has been more tireless in reviving the history of exhortations to join the “Order of Walkers” than the British editor and BBC producer Duncan Minshull. Back in 2000, he co-edited The Vintage Book of Walking: A Glorious, Funny and Indispensable Collection, which could also boast of being the most comprehensive anthology of such proselytizing, spanning fiction and nonfiction. It was reissued in 2014 as While Wandering: A Walking Companion.

This story is from the August 2019 edition of The Atlantic.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the August 2019 edition of The Atlantic.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

JOE ROGAN IS THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA NOW

What happens when the outsiders seize the microphone?

MARAUDING NATION

In Trumps second term, the U.S. could become a global bully.

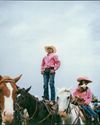

BOLEY RIDES AGAIN

America’s oldest Black rodeo is back.

THE GENDER WAR IS HERE

What women learned in 2024

THE END OF DEMOCRATIC DELUSIONS

The Trump Reaction and what comes next

The Longevity Revolution

We need to radically rethink what it means to be old.

Bob Dylan's Carnival Act

His identity was a performance. His writing was sleight of hand. He bamboozled his own audience.

I'm a Pizza Sicko

My quest to make the perfect pie

What Happens When You Lose Your Country?

In 1893, a U.S.-backed coup destroyed Hawai'i's sovereign government. Some Hawaiians want their nation back.

The Fraudulent Science of Success

Business schools are in the grips of a scandal that threatens to undermine their most influential research-and the credibility of an entire field.