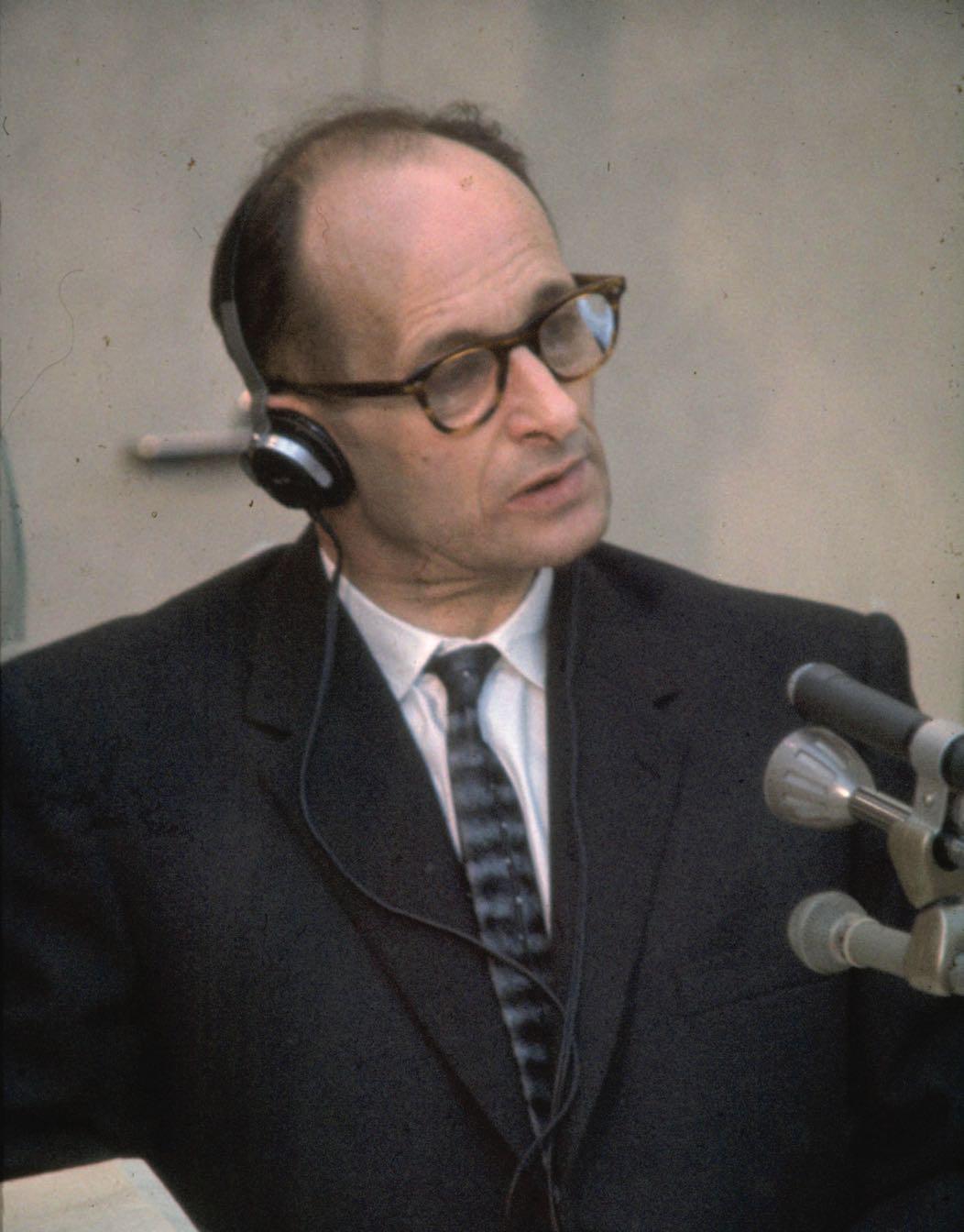

On the evening of 11th May 1960, the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad grabbed Adolf Eichmann off a street in a quiet district of Buenos Aires. Eichmann, formerly an SS officer and administrator, had been the key figure in organising the transportation of millions of Jews across Europe to the Nazi concentration camps. It was no wonder that Mossad wanted a word with him.

Upon capture, he was flown to Israel, and taken to trial on the 11th April 1961. The New Yorker commissioned the German Jewish political thinker Hannah Arendt to cover the trial. The trial ended in December 1961 with Eichmann's conviction for "crimes against the Jewish people, crimes against humanity, and war crimes during the whole period of the Nazi regime." Arendt's report, based on her observations of the defendant and of the conduct of the trial, was published in 1963 in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.

In her report, Arendt grappled with an enigmatic question: can one commit evil deeds without being innately evil? Her conclusion was a shocking and provocative theory which defied the conventional representation of evil as exceptional and demonic. Arendt did not see in Eichmann the monstrosity of a psychopath, but rather the mediocrity of a bland, mundane, unimaginative human being who, in her words, was "neither perverted nor sadistic... but terribly and terrifyingly normal" (p.276). According to Arendt, Eichmann had not recognised the atrocity of his acts due to a particular "inability to think, namely, to think from the standpoint of somebody else" (p.49). On the basis of what she saw and heard at the trial, she concluded that while acts of evil can result in monumental tragedies, the perpetrators of these acts need not in every case be inherently evil people. They may have motives they do not recognise as evil, and which may, indeed, be 'banal'.

This story is from the October/November 2023 edition of Philosophy Now.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the October/November 2023 edition of Philosophy Now.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

Metaphors & Creativity

Ignacio Gonzalez-Martinez has a flash of inspiration about the role metaphors play in creative thought.

Medieval Islam & the Nature of God

Musa Mumtaz meditates on two maverick medieval Muslim metaphysicians.

Robert Stern

talks with AmirAli Maleki about philosophy in general, and Kant and Hegel in particular.

Volney (1757-1820)

John P. Irish travels the path of a revolutionary mind.

IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE

Becky Lee Meadows considers questions of guilt, innocence, and despair in this classic Christmas movie.

"I refute it thus"

Raymond Tallis kicks immaterialism into touch.

Cave Girl Principles

Larry Chan takes us back to the dawn of thought.

A God of Limited Power

Philip Goff grasps hold of the problem of evil and comes up with a novel solution.

A Critique of Pure Atheism

Andrew Likoudis questions the basis of some popular atheist arguments.

Exploring Atheism

Amrit Pathak gives us a run-down of the foundations of modern atheism.