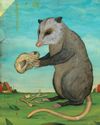

How Jorge Barón Biza put his family—and his fears—on the page.

The Argentine writer Jorge Barón Biza once said that his parents didn’t have a marriage so much as a “passionate, infinite divorce.” His father, Raúl Barón Biza, once chased his mother, Rosa Clotilde Sabattini, with a gun and thirty-two bullets; later, Raúl ran, still armed, into his in-laws’ house. (He told police that he had wished only to commit suicide.) Raúl was born in 1899, the scion of wealthy landowners in Argentina. After spending his twenties partying, he began publishing novels. He also got involved in politics, which is how he met Clotilde. She was the daughter of Amadeo Sabattini, a famous politician whose party, the Radical Civic Union (U.C.R.), controlled Argentina’s government throughout the twenties; it was removed from power, in 1930, in a military coup. By 1936, Raúl had married Clotilde and been accused of financing the leftist resistance. He invested in olive oil and mining while editing papers that supported the nationalization of all means of production. Clotilde became a prominent feminist and academic, specializing in pedagogy. When a U.C.R. faction regained the Presidency, in 1958, she was appointed president of the National Council for Education.

Bu hikaye The New Yorker dergisinin August 6 - 13, 2018 sayısından alınmıştır.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Giriş Yap

Bu hikaye The New Yorker dergisinin August 6 - 13, 2018 sayısından alınmıştır.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Giriş Yap

The Puppet Masters - Compulsion, complicity, and the art of Bunraku.

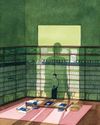

The National Bunraku Theatre, in New York recently for the first time in more than thirty years, presented an evening of suicides. The performance, at the Japan Society, consisted of excerpts from two of the company’s most celebrated productions. In the Fire Watchtower scene from “The Greengrocer’s Daughter,” by Suga Sensuke and Matsuda Wakichi, from 1773, the titular character sacrifices herself to save a temple page boy she loves. In a scene from “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki,” by Chikamatsu Monzaemon, from 1703, two lovers are driven to take their own lives. Both plays were inspired by real events, and Chikamatsu’s was followed by a wave of double suicides that led to a ban on further performances. This mirroring of life and art is all the more astonishing given the fact that the actors are not people but puppets.

The Convert - The sudden rise of J. D. Vance has transfixed conservative élites. Is he the future of Trumpism?

Vance’s selection as Trump’s running mate had punctuated an astounding rise. Born in the small manufacturing city of Middletown, Ohio, he was raised by a drug-addicted mother and his beloved Appalachian-born grandmother, Mamaw. He worked his way up through storied American institutions: the Marine Corps, Yale Law School, Silicon Valley. “Hillbilly Elegy,” the best-selling memoir Vance published in 2016, made him famous, and his denunciations of Trump as “cultural heroin” for the white working class even more so. A few years later, he was a senator from Ohio, the Republican Party’s most effective spokesman for Trumpism as an ideology, and—both improbably and inevitably—the VicePresidential nominee. “If you think about where he came from and where he is, at forty years old,” the conservative analyst Yuval Levin, a Vance ally, said, “J.D. is the single most successful member of his generation in American politics.”

SONGS OF WAR

Early on in “Blitz,” Rita Hanway (Saoirse Ronan), a London factory worker, puts her nine-year-old son, George (Elliott Heffernan), aboard a train. Rather, George puts himself aboard; he twists angrily free of his mother’s grasp—“I hate you!” he cries—and tears off down the platform.

STAR-CROSSED

“Sunset Blud.” and Romeo Juliet,” on Broadway.

A PIECE OF HER MIND

Does the Enlightenment’s great female intellect need rescuing?

EACH MORTAL THING

What other creatures understand about death.

From the Wilderness

One morning in the rainy season, I went to bed at 6 a.m. after working all night and was on the verge of falling asleep when I was startled by the sound of my father’s voice coming through the air-conditioner next to my bed.

THE BIG DEAL

Joe Biden's economic policies are starting to transform America. Will anyone notice?

THE LAST MILE

The aid workers who risk their lives to bring relief to Gaza.

TAKE ME HOME

The filmmaker Mati Diop turns her gaze on plundered art.