Revolution will come, someday, though I don’t know when,” said Shanti Munda, 78, one of the last surviving members of the Naxalbari uprising. Advanced age, multiple ailments, failing memory and financial woes have not dampened the spirit of this eternal optimist.

Munda lives in a frugal two-room house at Hatighisa village in the Naxalbari block of Darjeeling district in West Bengal. Her room is spartan, while the adjacent room is full of numerous awards her daughter won in athletics. Pictures of Jesus and Krishna adorn the room. Munda’s father had come from Jharkhand, and made his living by tilling the land. She got married in her teens. Her husband was revolutionary leader Keshav Sarkar, who also mentored her in peasant politics.

She recalled the time when protests were held against the jotedars (landowners) for exploiting the peasants. “My husband first told me about the exploitation,” she said. “Then Kanu da (revolutionary leader Kanu Sanyal) came and organised us. We demanded that instead of paying our share in rice, we should be paid money, which the zamindars did not agree to.”

On May 24 1967, she tied her 15-day-old daughter to her back, and joined the peasant revolt led by the armed tribals of Naxalbari against the atrocities committed by jotedars. “The police had gathered in Naxalbari thinking that senior communist leaders were hiding there,” said Munda. “A huge crowd of peasants—most of them women—had gathered. Some of them were over 80. I felt bad resting at home. So I went with my daughter. We had bow and arrows. We struck Sonam Wangdi, a police officer. He died.”

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber ? Sign In

This story is from the {{IssueName}} edition of {{MagazineName}}.

Start your 7-day Magzter GOLD free trial to access thousands of curated premium stories, and 9,000+ magazines and newspapers.

Already a subscriber? Sign In

William Dalrymple goes further back

Indian readers have long known William Dalrymple as the chronicler nonpareil of India in the early years of the British raj. His latest book, The Golden Road, is a striking departure, since it takes him to a period from about the third century BC to the 12th-13th centuries CE.

The bleat from the street

What with all the apps delivering straight to one’s doorstep, the supermarkets, the food halls and even the occasional (super-expensive) pop-up thela (cart) offering the woke from field-to-fork option, the good old veggie-market/mandi has fallen off my regular beat.

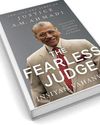

Courage and conviction

Justice A.M. Ahmadi's biography by his granddaughter brings out behind-the-scenes tension in the Supreme Court as it dealt with the Babri Masjid demolition case

EPIC ENTERPRISE

Gowri Ramnarayan's translation of Ponniyin Selvan brings a fresh perspective to her grandfather's magnum opus

Upgrade your jeans

If you don’t live in the top four-five northern states of India, winter means little else than a pair of jeans. I live in Mumbai, where only mad people wear jeans throughout the year. High temperatures and extreme levels of humidity ensure we go to work in mulmul salwars, cotton pants, or, if you are lucky like me, wear shorts every day.

Garden by the sea

When Kozhikode beach became a fertile ground for ideas with Manorama Hortus

RECRUITERS SPEAK

Industry requirements and selection criteria of management graduates

MORAL COMPASS

The need to infuse ethics into India's MBA landscape

B-SCHOOLS SHOULD UNDERSTAND THAT INDIAN ECONOMY IS GOING TO WITNESS A TREMENDOUS GROWTH

INTERVIEW - Prof DEBASHIS CHATTERJEE, director, Indian Institute of Management, Kozhikode

COURSE CORRECTION

India's best b-schools are navigating tumultuous times. Hurdles include lower salaries offered to their graduates and students misusing AI