CATEGORIES

Kategoriler

SNOOTY MOORE SCARES OFF THE GUYS!

DETERMINED Demi Moore was the talk of the Golden Globes for her snotty attitude toward Kylie Jenner, and sources dish she's equally full of herself when it comes to dating these days - and the lousy attitude is why the 62-year-old actress has had such poor luck snaring suitors! \"She's got an edge and she's intimidating to guys, plus she's a bit of a control freak and her dogs and daughters always come first,\" spills an insider.

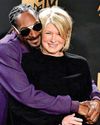

SNOOP DOGG HOUNDED TO DROP MARTHA!

His wife's had enough of domestic diva rival

DENISE ON HOOK FOR HUBBY'S MONEY MESS!

DRAMA magnet Denise Richards' dough may be in jeopardy as her wellness guru husband is being sued by a creditor and grappling with a fraud lawsuit that charges he refused a promised refund to a woman with terminal cancer, sources spill.

PRINCE WILLIAM'S PORNO PALACE!

PERVY Prince William’s secret penchant for porn is rocking an already rattled monarchy — and chatter about his horny habit is embarrassing the future king’s cancer-survivor wife, Kate, courtiers confide.

MUNIZ MOPES OVER MALCOLM REBOOT!

FORMER TV tyke Frankie Muniz was excited about doing a reboot of his hit series Malcolm in the Middle, but his cryptic social media comment on friendship — or the lack thereof — seems to suggest it's not going so well!

VULNERABLE VANNA PUSHES BEAU AWAY!

Gun-shy about pulling trigger on marriage

CHER NEEDS TO DITCH COUGAR ACT

She just can't turn back time with boytoy

ROCKY ROAD TO ROMANCE!

Two child stars from the 2003 hit School of Rock have tied the knot — even though they were NOT interested in making beautiful music together 22 years ago while filming the Jack Black movie!

PASSION RULES PARIS!

King of Pop daughter ready to skip prenup

Hugh Jackman & Sutton Foster What They Sacrificed for LOVE

THE MUSIC MAN CO-STARS HAVE ENDURED PAINFUL CHANGES IN THEIR LIVES TO BE TOGETHER

WHO KILLED Thelma Todd?

THE FILM COMEDIENNE TURNED RESTAURATEUR DIED AT AGE 29 UNDER SUSPICIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES

MISERY OVER BATES' RISKY BODY CHANGES!

Obsessed ex-pudgester won't budge over Ozempic

NIP-TUCK COOLIDGE SHOULD COOL IT!

Heading for plastic disaster

DENISE RICHARDS' HUBBY: MEDICAL SCAM?

Denise Richards' husband, Aaron Phypers, is facing some serious accusations.

Megan & MGK FAIR BATTLE OVER BABY!

Megan Fox and MGK are at odds over coparenting plans.

ARIANA'S AUDREY OBSESSION

During her extensive press tour for Wicked, Ariana Grande has shown up in a parade of exquisite throwback looks that have drawn comparisons to film legend Audrey Hepburn.

Al: GAGA OVER NOOR

AI Pacino's arrangement with baby mama ex Noor Alfallah - spoiling her with fancy dinners and attention -works just fine for him, thank you very much.

BROOKE SHIELDS AT 59 I'm Calling THE SHOTS

THE ACTRESS AND FORMER MODEL SHARES HER THOUGHTS ABOUT AGING IN A NEW BOOK

5 FOODS THAT EASE JOINT PAIN

YOUR DIET PLAYS A SIGNIFICANT ROLE IN REDUCING ARTHRITIS ACHES AND INFLAMMATION

OBAMA DIVORCE MAKES HISTORY

Glam couple’s stunning split blindsides the world

Positivity IS POWER

The talk show host opens up about his latest projects • and how he remains so vibrant despite MS

OHIO'S MISSING KIDS!

Mystery deepens as children vanish from small town

William & kate Crowning a New King and Queen

AS KING CHARLES III'S HEALTH DETERIORATES, THE PRINCE AND PRINCESS OF WALES ARE QUIETLY PREPARING TO TAKE OVER THE MONARCHY - AND MAKE CHANGES.

JESSICA IN PERIL WITHOUT ERIC TO LEAN ON!

0NETIME party girl Jessica Simpson and hubby Eric Johnson are finally ending their tumultuous decade-long marriage, and Hollywood sources say the breakup could send the country pop queen spiraling back into an abyss of boozing and pill-popping!

HORNDOG LEO STILL WON'T BE LEASHED!

HOLLYWOOD lothario Leo DiCaprio has turned 50 but still seems to have no intention of settling down, and pals of his latest plaything, Italian model Vittoria Ceretti, are said to be telling her not to waste any more of her precious youth on the notorious runaround.

CRUISE TAKES HIS OWN BREATH AWAY!

Goes deep into lung training for underwater role

BRODY BLASTS CAITLYN

Brody Jenner just opened up about his difficult relationship with his father, the Olympic gold medalist Bruce Jenner, who transitioned to Caitlyn Jenner in 2015.

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT!

It's hard to believe Renée Zellweger could go unnoticed.

Stars DEVASTATING LOSSES

THE WORST FIRES TO HIT LOS ANGELES HAVE LEFT MANY WITHOUT HOMES, INCLUDING THESE STARS, WHO FLED THE FLAMES.

CARRIE Does Hert Way!

SHE ALIENATEDSOME FANS AND FELLOWCELEBRITIES WITH HERPRESIDENTIALINAUGURATION PLANS.BUT COUNTRY STARCARRIE UNDERWOOD ISNO LONGER INTERESTEDIN PLAYING IT SAFE.